The Sensor Intel Series is created in partnership with Efflux, who maintains a globally distributed network of sensors from which we derive attack telemetry.

Introduction

The F5 Labs Sensor Intel Series provides an in-depth analysis of the most significant vulnerabilities and their exploitation trends. This article highlights the top 10 CVEs, their activity levels, and their potential impact on organizations. By examining long-term trends and recent activity, this report aims to inform security professionals about emerging threats and provide actionable insights for mitigating risks.

Trending CVEs for January

CVE-2017-9841, a PHPUnit Remote Code Execution (RCE) vulnerability, continues to see widespread exploitation. This vulnerability allows attackers to execute arbitrary code on affected systems. Organizations using outdated PHPUnit versions should update to the latest version immediately and review their systems for signs of compromise.

CVE-2025-55182, a React Server Components Unsafe Deserialization RCE, has emerged as a critical threat. This vulnerability allows attackers to execute malicious code by exploiting unsafe deserialization in React Server Components. Developers should apply the latest patches and review their code for secure deserialization practices.

CVE-2019-9082, a ThinkPHP PHP Injection RCE, remains a significant concern. This vulnerability enables attackers to inject malicious PHP code into ThinkPHP applications. Organizations using ThinkPHP should update to the latest version and implement input validation to prevent exploitation.

CVE-2024-4577, an Apache PHP-CGI Argument Injection RCE, has seen increased activity. This vulnerability allows attackers to inject arguments into PHP-CGI scripts, leading to arbitrary code execution. Administrators should apply the latest patches and configure their servers to mitigate this risk.

CVE-2022-24847, a GeoServer JNDI Lookup RCE, continues to be exploited. This vulnerability allows attackers to execute arbitrary code via JNDI lookups in GeoServer. Organizations using GeoServer should update to the latest version and disable JNDI lookups if not required.

GeoServer Targeting on the Rise

F5 Labs sensors recorded a 50% increase in activity targeting GeoServer-related paths in January 2026 compared to December. While GeoServer is not new, its internet-facing footprint remains large, and recent vulnerability disclosures have kept it on the radar for opportunistic scanning and exploitation. In January’s data, requests clustered around three themes: OGC (Open Geospatial Consortium) service probing (especially WFS), discovery of the GeoServer web interface, and validation of WMS endpoints.

This matters because the early stages of targeting often look mundane in isolation. A single request for WFS capabilities or a hit on /geoserver/ does not tell you much. In aggregate, repeated access to service discovery endpoints, UI paths, and operations like WMS GetMap can indicate an actor preparing for follow-on activity: capability and layer enumeration, testing for vulnerable code paths, and, in some cases, delivery of exploit payloads.

Two vulnerabilities help explain why GeoServer can see sudden swings in attention. CVE-2025-58360, disclosed in late 2025 and reported as exploited, describes an unauthenticated XML External Entity issue associated with WMS GetMap processing that can lead to file disclosure, SSRF, or denial of service. CVE-2024-36401 describes unauthenticated remote code execution through crafted input against multiple OGC operations. Even when a scanner is focused on one issue, tooling often bundles checks for several historical CVEs, which keeps older GeoServer issues relevant well after their publication.

The emphasis in this article is a defender-focused view of the targeting patterns we observed in January 2026, what those requests tend to look like in real-world logs, and what actions can reduce risk quickly if you operate GeoServer.

Why GeoServer Keeps Showing Up in Internet Scanning

GeoServer is an open-source server used to publish and manage geospatial data. It is commonly deployed to support OGC standards such as Web Map Service (WMS), Web Feature Service (WFS), and OGC Web Services (OWS), which provides a shared endpoint for multiple service types. In many environments GeoServer is intentionally exposed to the public internet to enable map viewing, feature queries, and integration with third-party GIS tooling.

That exposure is also what makes GeoServer attractive. The platform offers a broad set of operations and data formats and can accept complex inputs. From an attacker’s perspective, it presents a set of endpoints that are easy to fingerprint remotely, and a parsing surface where implementation mistakes can have outsized impact. For defenders, the key point is that GeoServer is not just another web application. It is an application that exposes specialized interfaces that most organizations do not monitor with the same care as conventional login portals and APIs.

In January, the targeting we observed did not focus on only one part of the stack. Instead, it combined UI discovery with repeated OGC service operations. That combination is often a sign of tool-driven activity: confirm the product, verify which services are enabled, then test for behaviors linked to known vulnerabilities.

January 2026 at a Glance

Across the sensors, GeoServer-related activity increased by 50% in January 2026 compared to December. The traffic was predominantly GET-based, but also included a meaningful amount of POST activity:

- GET: 93%

- POST: 7%

Even when GET dominates, POST volume matters because many higher-impact interactions with GeoServer, including some OGC operations and vulnerability probes, are easiest to deliver via request bodies.

The most frequently requested URIs in January reflect a consistent set of actor priorities. The top request by far was a WFS 2.0 operation that enumerates stored queries. The next tier was made up of direct requests to the GeoServer web interface and common “landing” pages, followed by OWS and WFS capabilities checks and repeated access to WMS endpoints.

Paths observed:

- WFS probing and enumeration

- /geoserver/wfs?request=ListStoredQueries&service=wfs&version=2.0.0

- /geoserver/ows?service=WFS&request=GetCapabilities

- /geoserver/wfs?service=WFS&request=GetCapabilities

- Web UI and framework discovery

- /geoserver/web/

- /geoserver/web/wicket/bookmarkable/org.geoserver.web.AboutGeoServerPage

- /geoserver/web/wicket/bookmarkable/org.geoserver.web.demo.MapPreviewPage

- WMS validation and map retrieval

- /geoserver/wms

- /geoserver/wms/

- ...request=GetMap...

There were also a few low-volume but meaningful probes:

- /geoserver/j_spring_security_check (authentication handler)

- /geoserver/TestWfsPost (testing POST behavior)

- /geoserver/rest.html (REST documentation surface)

Taken together, these requests show a consistent approach: identify and map the target, validate which GeoServer components and services respond, and enumerate WFS and WMS operations that are most likely to lead to deeper interaction.

What the Targeting Looked Like on the Wire

A useful way to interpret these requests is as a sequence rather than a flat list.

The starting point is basic application discovery. Hits on /geoserver/ and /geoserver/index.html are the kind of checks a scanner makes when it is sweeping common product paths across the internet. The web UI paths that follow, particularly /geoserver/web/, are notable because most normal programmatic use of GeoServer does not require the interactive UI. Attackers and scanners, by contrast, frequently hit UI resources because they can reveal version information, enabled modules, or configuration characteristics that help decide whether exploitation is worth attempting.

The presence of Wicket bookmarkable URLs, such as the About page and Map Preview page, adds weight to the “purpose-built tooling” conclusion. These are not generic paths a random crawler would stumble into. They are recognizable GeoServer web application routes that are useful for verifying identity and gathering context. The Map Preview page in particular showed repeated requests that included URL-based session identifiers:

- /geoserver/web/wicket/bookmarkable/...MapPreviewPage;jsessionid=$COOKIE?0

- /geoserver/web/wicket/bookmarkable/...MapPreviewPage;jsessionid=$COOKIE?1

URL-based jsessionid usage is a known pattern in Java applications. In hostile traffic it often appears as a templated probe to see how the server handles session identifiers embedded in the path, or as part of a generic Java web scanning module. Regardless of the motive, it is rarely a sign of legitimate user-driven activity.

Alongside UI requests, scanners repeatedly queried OGC capabilities. Requests like GetCapabilities allow a client to identify what the server supports and, depending on configuration, can expose layer names, namespaces, feature types, and supported output formats. That information is valuable for legitimate GIS integration, but it is also what an attacker needs to craft follow-on requests that hit more complex parsing logic.

In January, the most common operation was ListStoredQueries for WFS 2.0. WFS stored queries can be used legitimately, but repeated enumeration at scale is more consistent with automated probing. Once an actor confirms WFS behavior and supported versions, the next step is typically to move into feature retrieval operations or to begin testing malformed or crafted parameters against deeper request-processing paths.

Finally, we observed consistent WMS endpoint probing. That included direct hits on /geoserver/wms and /geoserver/wms/, as well as GetMap operations. One request pattern included the commonly seen topp:states layer parameters, a sample layer frequently present in documentation and example configurations. That does not prove a default installation, and many scanners use it as a generic test case whether or not the layer exists. The point is the same: validate that WMS is reachable and then attempt operations that trigger deeper request handling.

Tooling Signals in User Agents

User agents in hostile traffic are no longer a reliable divider between “automation” and “human.” In January’s GeoServer-related requests, the most common user agents presented as mainstream browsers, often using generic or incomplete Chrome and WebKit strings. Older browser versions were common, and there was also a smaller set of requests using headless tooling indicators. A meaningful number of requests used a missing or blank user agent.

This mix is consistent with widely available scanning and exploitation toolkits that spoof common user agents to avoid trivial filtering and to blend into baseline web traffic. The practical defender takeaway is straightforward: focus your detection on request sequences, rate, and endpoint patterns, not on whether the user agent looks like a browser.

Why the Spike Now

It is reasonable to ask why GeoServer, an established and widely deployed product, would see a 50% month-over-month increase in targeting in January 2026.

One driver is the vulnerability disclosure cycle. When a critical vulnerability is published and widely discussed, scanning volumes rise as attackers and researchers refresh inventories of exposed systems and test for patch lag. That effect is often delayed and uneven. Even if a vulnerability is disclosed in late 2025, scanning can surge into early 2026 as tooling is updated, exploit writeups spread, and opportunistic actors incorporate new checks into broad “spray and scan” workflows.

Another driver is that GeoServer vulnerabilities tend to map to easily tested surfaces. OGC operations are predictable and standardized, which makes it convenient to build generic probes. An actor can test whether a target is GeoServer and whether WFS or WMS is enabled with a handful of requests and then pivot into more complex operations if the target appears promising.

Finally, attackers rarely scan for just one CVE. Once a scanner has confirmed a GeoServer-like surface, it often runs a bundle of checks that spans several years of vulnerabilities and misconfigurations. That is one reason older GeoServer issues can continue to show up as “background” even when a newer CVE is the event that triggered renewed attention.

For January 2026, two vulnerabilities are particularly relevant to defenders and help explain the combination of WMS and WFS activity.

What the High-Impact CVEs Look Like in Logs

CVE-2025-58360: XXE via WMS GetMap

CVE-2025-58360 has been described as an unauthenticated XML External Entity vulnerability associated with WMS GetMap processing. XXE issues are not just about crashing parsers. They can be abused to read local files, induce server-side requests to internal systems, or cause denial-of-service conditions. From an incident response perspective, the most important point is that XXE can produce evidence outside the application logs, especially if SSRF is involved.

In your logs, activity that aligns with WMS-focused probing tends to show up as:

- Direct endpoint checks:

- GET /geoserver/wms

- GET /geoserver/wms/

- Standard map retrieval templates, often repeated with small variations:

- GET /geoserver/wms?service=WMS&version=1.1.0&request=GetMap&layers=...

- Tooling mistakes or generic parameter mixing:

- GET /geoserver/wfs?service=WMS&request=GetMap

These requests alone do not confirm exploitation. What typically separates routine service validation from attempts to trigger vulnerable parsing is what happens next. Defenders should look for patterns such as:

- A shift toward POST requests targeting WMS or shared OWS endpoints shortly after WMS discovery traffic appears.

- Sudden spikes in 4xx and 5xx responses during short bursts of WMS traffic. Parsing-oriented attacks commonly generate errors before a successful payload is found.

- Unusual content types associated with XML submission, especially if your environment normally sees only simple image/png responses for map tiles.

- Correlated egress anomalies from the GeoServer host. If an XXE payload induces SSRF, you may see new outbound connections or DNS lookups that line up with inbound WMS request spikes.

If you operate GeoServer behind a reverse proxy, you can often add immediate value by logging request sizes and content types for WMS and OWS endpoints. Those metadata fields are frequently enough to distinguish “is WMS alive” probes from “is WMS parsing attacker-controlled XML” attempts, even if you do not capture request bodies.

CVE-2024-36401: Unauthenticated RCE Through OGC Request Parameters

CVE-2024-36401 has been described as an unauthenticated remote code execution issue reachable through crafted input in multiple OGC operations. The important operational consequence is that the attack surface is broad. Defenders should not focus exclusively on a single path like /geoserver/wfs. A scanner may start with WFS capabilities, but the exploitation attempt could be delivered through WMS or another OGC endpoint depending on what the tool supports.

In logs, the early phase often resembles what we observed at scale:

- Capabilities checks:

- GET /geoserver/ows?service=WFS&request=GetCapabilities

- GET /geoserver/wfs?service=WFS&request=GetCapabilities

- Deeper WFS probing:

- GET /geoserver/wfs?request=ListStoredQueries&service=wfs&version=2.0.0

From there, defenders should be alert for a rapid escalation into operations that force deeper parsing and evaluation. Even without enumerating every possible operation, you can characterize likely exploit traffic by how it behaves:

- Short sequences where the same source IP hits multiple GeoServer service endpoints within seconds.

- Requests that rapidly vary version parameters, service parameters, and operation names.

- Unusually long query strings or heavily encoded parameter values, especially when they appear where a simple layer name or property name would normally be expected.

- POST requests into OWS-related endpoints shortly after capability and stored-query enumeration.

If you have WAF telemetry, this is where it often becomes useful. Many exploitation attempts for request-parameter issues involve payload elements that look like expression syntax rather than typical GIS parameters. Even if the WAF cannot conclusively identify the CVE, it can help you spot abnormal payload shapes.

Other Issues Attackers May Include in Bundled Scanning

Once GeoServer is identified, some tools will also check for secondary issues and misconfigurations. For example, recent releases have addressed a reflected XSS issue (CVE-2025-21621), and some disclosures are more relevant to particular deployment patterns such as Windows-based installations. These do not map as cleanly to the URI patterns in January’s data, but they are part of why GeoServer scanning rarely stays confined to one operation or one year’s CVEs.

The practical approach for defenders is to treat GeoServer targeting as a family of behaviors. A tool that starts with WFS enumeration can pivot into WMS operations, UI endpoints, authentication probes, and REST documentation checks in one sweep.

What Defenders Should Look For in Their Own Environments

If you run GeoServer, the easiest way to start is to decide which surfaces should be reachable from untrusted networks. Then search your logs for evidence that those surfaces are being actively targeted.

The following are useful pivots because they are common in scanning sequences and are not always present in everyday usage:

- WFS stored query enumeration:

- /geoserver/wfs?request=ListStoredQueries&service=wfs&version=2.0.0

- Capabilities enumeration across OWS and WFS:

- /geoserver/ows?...GetCapabilities

- /geoserver/wfs?...GetCapabilities

- Web UI and Wicket bookmarkable pages:

- /geoserver/web/

- /geoserver/web/wicket/bookmarkable/...

- WMS endpoint checks and GetMap activity:

- /geoserver/wms

- any request=GetMap activity, especially if it appears in unusual combinations

- Authentication handler probes:

- /geoserver/j_spring_security_check

When you pivot on these, look for clustering. The strongest signals are usually not single requests, but patterns: repeated hits in a short time window, repeated parameter variation, and the same client touching both UI paths and OGC service operations.

If you can, add correlation with network telemetry. For potential XXE and SSRF patterns, outbound DNS and HTTP logs from the GeoServer host can provide evidence that never appears in web access logs.

Mitigation and Hardening Actions

GeoServer deployments vary widely, but there are a few controls that reduce exposure regardless of the specific CVE an attacker is attempting.

Patch aggressively. Recent GeoServer vulnerabilities have included critical issues affecting default installations and common OGC operations. The best defensive posture is to track GeoServer security advisories and apply updates promptly, especially when unauthenticated issues affecting WMS, WFS, or OWS endpoints are fixed.

Reduce the exposed surface. Many environments expose OGC services publicly but do not need to expose the administrative UI. If /geoserver/web/ is reachable from the internet, consider restricting it to trusted networks. The same applies to any administrative or REST-related surfaces. Even when access is protected by authentication, reducing exposure lowers the chance that an attacker can exercise vulnerable code paths or harvest information.

Add guardrails at the edge. Rate limiting and request size controls are often effective against high-volume scanning and some classes of parser abuse. If you operate a WAF or reverse proxy in front of GeoServer, log and monitor unusual content types and sudden shifts in POST activity to OWS and WMS endpoints.

Control egress where possible. XXE and SSRF risks are reduced when the GeoServer host cannot initiate arbitrary outbound connections. Egress filtering, DNS monitoring, and alerting on unexpected outbound destinations can limit the impact of exploitation even when an attacker finds a viable payload.

Make sure you have logs you can use. At a minimum, ensure you are retaining reverse proxy logs for GeoServer paths and that they include source IP, URI, method, response code, and user agent. If you can add request size, content type, and latency, those fields are often decisive when investigating suspected exploitation attempts.

Summary

January 2026 saw a notable increase in requests targeting GeoServer-related paths and OGC operations across F5 Labs sensors. The most common patterns focused on WFS enumeration, repeated mapping of the GeoServer web interface, and validation of WMS endpoints. This blend of activity aligns with the way opportunistic scanners and exploitation toolchains operate: confirm the product, enumerate services, and then probe the operations most likely to expose vulnerable parsing logic.

For defenders, the right response is not to debate whether any single request is benign. GeoServer is being actively targeted on the public internet, and recent high-impact vulnerabilities give attackers good reasons to keep testing it. If GeoServer is part of your environment, treat January’s rise as a prompt to validate patch levels, reduce exposed surfaces, and ensure you can detect and investigate OGC service abuse quickly.

Top CVEs for January

In January 2026, CVE-2017-9841 remains the most exploited vulnerability, with over 70,000 instances of exploitation attempts (as shown in Table 1). CVE-2025-55182 follows with nearly 20,000 instances, reflecting its critical severity and high exploitation potential. CVE-2019-9082, CVE-2024-4577, and CVE-2022-24847 also show significant activity, with thousands of exploitation attempts each. Notably, CVE-2023-1389 has dropped to seventh place, indicating a decline in activity. The table underscores the importance of addressing these vulnerabilities to mitigate potential risks.

| # | CVE ID | CVE NAME | JANUARY Traffic | CVSS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1– | CVE-2017-9841 | PHPUnit eval-stdin.php RCE | 70867 (+13340) | 9.8 |

| 2– | CVE-2025-55182 | React Server Components Unsafe Deserialization RCE | 19624 (+4158) | 10.0 |

| 3↑ | CVE-2019-9082 | ThinkPHP PHP Injection RCE | 4152 (+780) | 8.8 |

| 4↑ | CVE-2024-4577 | Apache PHP-CGI Argument Injection RCE | 4089 (+725) | 9.8 |

| 5↑ | CVE-2022-24847 | GeoServer JNDI Lookup RCE | 2455 (-4) | 7.2 |

| 6↑ | CVE-2025-31324 | SAP NetWeaver Metadata Uploader Unauthenticated Upload | 2118 (+127) | 9.8 |

| 7↓ | CVE-2023-1389 | TP-Link Archer AX21 Command Injection RCE | 2101 (-6207) | 8.8 |

| 8↓ | CVE-2022-42475 | FortiOS FortiProxy SSL-VPN Heap Overflow RCE | 2053 (+30) | 9.8 |

| 9– | CVE-2022-22947 | Spring Cloud Gateway Actuator Code Injection RCE | 2049 (+127) | 10.0 |

| 10– | CVE-2022-47945 | ThinkPHP Lang Parameter LFI RCE | 1817 (+317) | 9.8 |

Table 1: Top 10 CVEs for April 2025. CVSS scores are v3.1. All data is as of 01/02/2026.

Long Term Targeting Trends

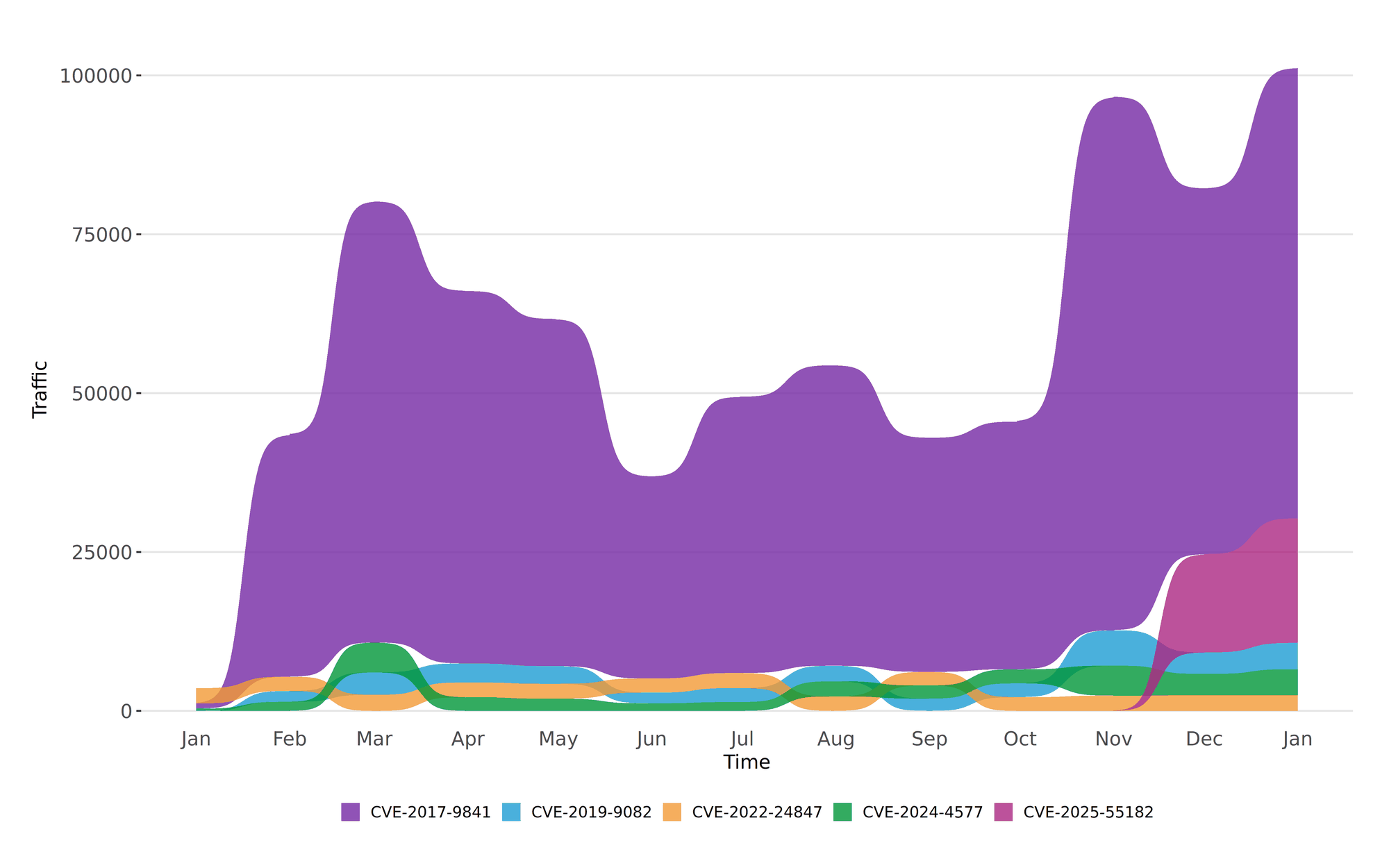

CVE-2017-9841 continues to dominate the top spot with a significant increase in activity, reaching 70,867 instances in January 2026 (see Figure 1). CVE-2025-55182 maintains its position in second place, with a notable rise in activity to 19,624 instances. CVE-2019-9082 and CVE-2024-4577 have both climbed in rankings, showing increased activity levels. CVE-2022-24847 rounds out the top five, although its activity has slightly decreased compared to the previous month. These trends highlight the persistent exploitation of certain vulnerabilities and the emergence of new threats.

Figure 1: Twelve-month bump plot of the top 5 CVEs.

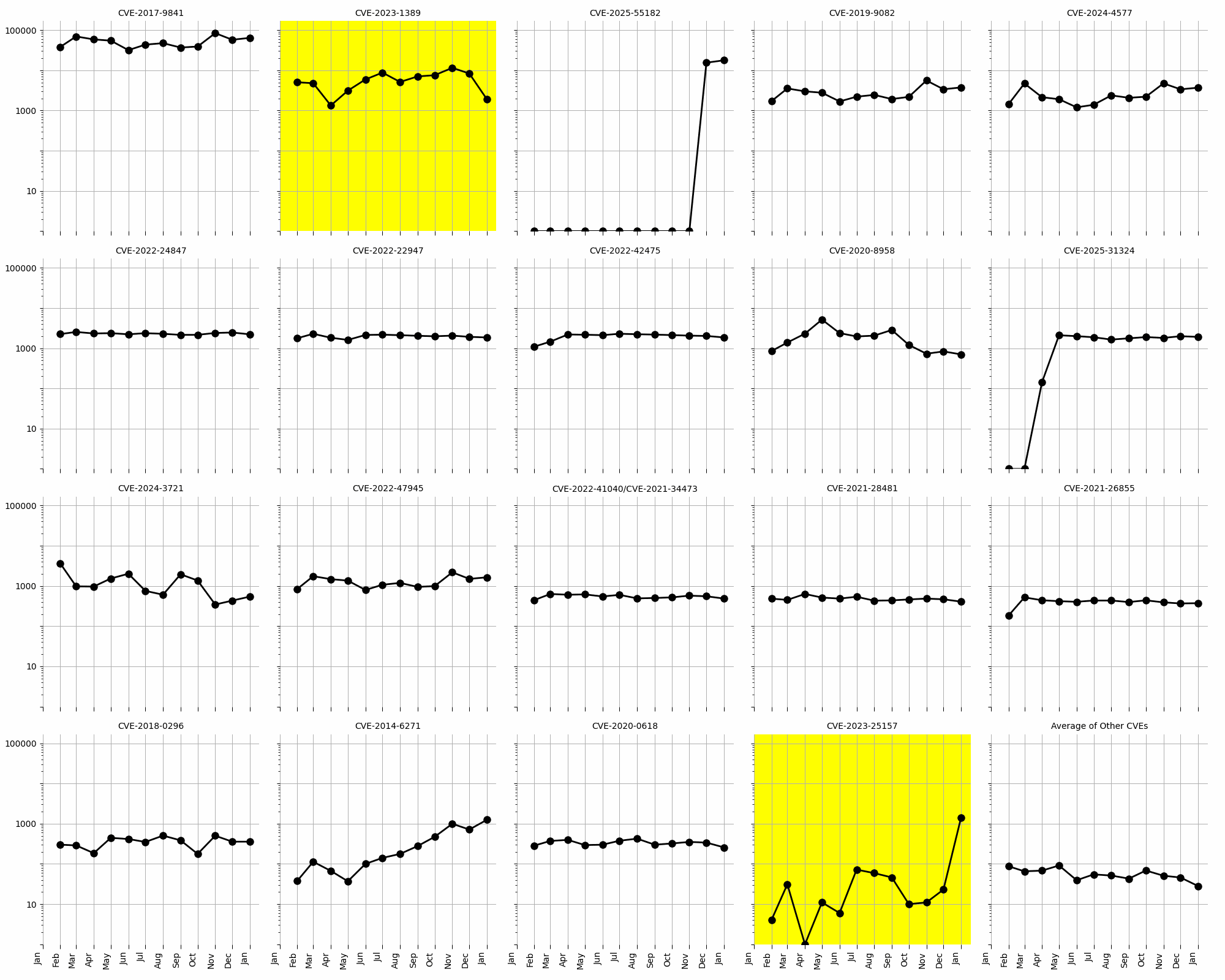

Two CVEs stand out in the long-term trends for January 2026 (see the logarithm scale plots in Figure 2). CVE-2023-1389, which previously showed high activity, has seen a significant decline in exploitation attempts, dropping from 8,308 in December 2025 to 1,897 in January 2026. This suggests that mitigation efforts or patching may have been effective. On the other hand, CVE-2023-25157 has shown a steady increase in activity, rising from 23 in December 2025 to 1,416 in January 2026. This indicates growing interest or exploitation attempts, warranting immediate attention to address this vulnerability.

Figure 2: Evolution of vulnerability targeting in the last twelve months, shown using a logarithmic scale for ease of comparison.

Conclusion

The analysis of January 2026 data reveals persistent exploitation of certain vulnerabilities, such as CVE-2017-9841, and the emergence of new threats, such as CVE-2025-55182. While some vulnerabilities, like CVE-2023-1389, have seen a decline in activity, others, like CVE-2023-25157, are gaining traction. Organizations must prioritize patching and implementing security measures to address these vulnerabilities and reduce their exposure to potential attacks.

Recommendations

- Scan your environment for vulnerabilities aggressively.

- Patch high-priority vulnerabilities (defined however suits you) as soon as feasible.

- Engage a DDoS mitigation service to prevent the impact of DDoS on your organization.

- Use a WAF or similar tool to detect and stop web exploits.

- Monitor anomalous outbound traffic to detect devices in your environment that are participating in DDoS attacks.