It’s an unfortunate reality that all CISOs must face: security tools sometimes don’t work as planned. The savvy CISO knows better than to believe vendor claims of perfect fixes. However, it’s not always the product that falls short of its mark; sometimes controls just aren’t fully deployed. In worst cases, some control solutions operate so poorly that they are bypassed, creating additional risk.

How prevalent is this problem? One survey found that nearly a third of security dollars are spent on security solutions that go unused or under-utilized.1 It’s hard enough to get resources to deploy risk mitigating controls, but it is discouraging to hear how those resources are being wasted. This isn’t a problem unique to security. Another survey found that project failure within IT affects more than half of businesses surveyed.2 As we say here at F5 Labs, you cannot throw sod down on cement and hope it will grow.

There are many reasons security projects fail to thrive. One reason that is not well-examined is simplistic and shallow planning. This disconnect begins when planning is done purely from a technical perspective, and often with idealized assumptions about how things work. Some architects assume their enterprise systems are clean, simple, well-defined architectures with disciplined users performing defined operations within the system. They erroneously assume that if they make a little change, there will be little or no blowback within the enterprise. This is not always the case.

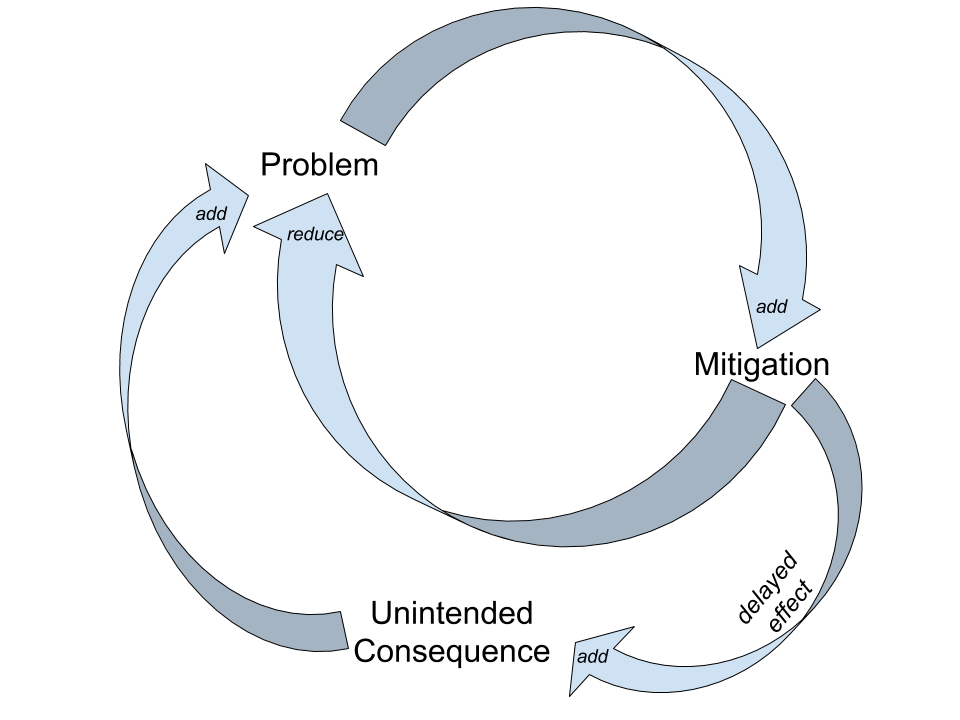

In the real world, most IT infrastructures are complex Rube Goldberg machines composed of a tapestry of piecemeal designs and multiple point solutions stitched together over time. On top of that, these IT systems are also interwoven with dynamic “out of scope” processes such as legal, business, social, and financial subsystems. Many of these variables and subsystems can affect each other with delayed and non-direct feedback loops. How can there ever be “one little change” to such a complex system without unforeseen effects? Small events that are separated by distance and time can cause significant upheaval in complex systems. Worse, as problems mount, the use of the same poorly fitting fix over time can create more and more unintended consequences that silently build up to a major new problem.

To treat complex systems as simple machines is to invite unnecessary delay or, worse, project failure. A better way of planning is to embrace the complexity and model it using a holistic systems approach. This means to acknowledge, examine, and incorporate those “invisible” factors and their relationships. A discipline called Systems Theory offers guidance on how to do this. Here are some basic tenets of Systems Theory:

- Systems have context and history: the past is integrated into the present

- Systems have many connected levels or facets that constrain and compel each other

- A minor change could produce major consequences, therefore everything has trade-offs

- Systems maintain equilibrium and are governed by feedback

Through the lens of Systems Theory, you can view your organization’s IT infrastructure as a constant interaction of users, business needs, technology changes, and cultural context. There are also external feedback loops, direct and indirect, that pass in and out of the organization, such as relationships to customers, vendors, and regulatory agencies. While these things need not be modeled, they still exist, and you should be prepared for possible changes. Altering the behavior of a system involves monitoring and adjusting the interaction rates between the different subsystems.

Let’s move away from the abstract and nail this down with some pragmatic specifics. The normal practices of a CISO would stay the same, but it is in thoughtful application based on these dynamic factors that new leverage is gained. Per Systems Theory, there are specific ways to alter a system. Below are system theory adjustment methods mapped to common techniques in the CISO toolkit.

| Systems Adjustment Tool | Security Program Example |

| Adjust parameter for rate of change | Bug bounties, deployment process, rollout of controls |

| Alter the rules | Security policy, approval process, ownership of assets/risk |

| Adjust buffers and flows | Budget, workload, personnel |

| Regulate feedback loops (positive, negative, delays) | Audits (internal/external), awareness rewards |

| Alter information flows | Make things visible/invisible (risk or compliance scorecards, shared cost) |

| (Re)define the goals/paradigm | Define and share acceptable risk, define security culture, lead by example |

The CISO can use these techniques to adjust the appropriate subsystems to move and maintain interactions to the desired level. Let’s unpack an example of doing this.

Here’s a common security problem: applications and data are spread around everywhere—on the local networks, on laptops at home, on personal machines, on mobile devices, and in the cloud (both approved and unknown). You and the CIO are trying to clamp down and get it under control, but it’s taking a long time. Then the audit findings slam down onto your desk like a pallet of concrete blocks. What do you do? Implement Digital Leak Prevention, tough new security policy, and put everyone through mandatory security usage training? Sure, but to paraphrase a famous princess: The more you tighten your grip, the more systems will slip through your fingers.

Before acting, you can step back and examine the situation at all levels. As the famous Systems Theory guru Gerald Weinberg said, “Things are the way they are because they got that way.”3

This kind of problem is usually one that crept up over the years, often as a reaction to users having limited access to the tools they feel they require for their jobs. It’s highly likely they want to work on their data with the appropriate applications anytime, anywhere. This is not a bad thing and makes sense as a business need. Granted, there are risks that need to be mitigated.

Stepping back again to look at the big picture you ask: what is really at stake here? Company data needs protection. The primary risk is unauthorized access to that data beyond your organization’s borders. Once data leaves your walls, you’ve lost any semblance of real access control. Therefore, you’d need to map out the user needs and find appropriate secure solutions (insourced or outsourced) to those needs. Likely the CIO can help. Your job would be blessing the solutions that meet your security requirements. It’s not easy, but it’s a problem that is solvable, and with the plethora of SaaS vendors offering secure solutions, not infeasible. Second, the best control we have when we outsource is good authentication. To make it easier for the users and to meet your audit requirements, an easy path is federated authentication. This can also help drive the vendor selection process. Once you’ve got auditor buy-in to the solution, it’s time to roll this out.

Before you pull the trigger, remember the tactics for altering a system. You’d want to present this as a positive to the users and offer an amnesty program for anyone already violating policy. Start with a briefing to explain the risk and audit reasons behind why you’re doing this (Redefine the goals/paradigm) and the new security policy (Alter the rules). Explain that anyone using the blessed applications will get full IT support for the migration. On the back channel, you work with Finance to shut down expense reimbursements to non-blessed shadow IT (Regulate feedback loops).

System theory says things take time to flow from one state to another, so this adoption won’t happen overnight. Make sure the auditors and management know this and don’t have unrealistic expectations. A good way to ensure an orderly migration is to shorten the feedback loop so you catch problems early. Start small with a pilot and test, adjust, expand as you see success (Adjust parameter for rate of change).

In the end, you still probably won’t get 100 percent compliance. All things being equal, you’re likely to hit 80 percent adoption on the first run through with a long tail of slow adoption after that. So, plan for that as well. Publish organization-wide metrics on adoption (Alter information flows) so folks can see how well they’re doing. If they know they’re being measured and can see how their peers are doing, you’ll build momentum. For the final group of misfit applications/users, you can assemble a temporary task force to identify and assist them over the final hump (Adjust buffers & flows).

Through the lens of Systems Theory, security is an emergent property of a system, not an add-on that can be bolted on when needed. Organizations are in constant motion at many layers. Plan for this and your security control deployments will work more successfully.