It seems like threat actors everywhere could detect my impatience last month when I wrote that not much had changed among the 70-odd CVEs that we track for attack trends, because last month they did something. Actually, to be more precise, they stopped doing some things. This is the first month since September 2022 that CVE-2020-8958, the GPON router OS command injection flaw, was not the top-targeted CVE. Let’s see what CVE took its spot, and which other CVEs changed in July.

July Vulnerabilities by the Numbers

Figure 1 shows the volume of attack traffic for the top ten vulnerabilities in July. In place of CVE-2020-8958, CVE-2017-9841, a remote code execution vulnerability in PHPUnit, took the top spot. We also added a new CVE to our signatures in July, which promptly landed in the fifth spot for the month: CVE-2022-42475, a buffer overflow vulnerability in various versions of Fortigate’s FortiOS and FortiProxy SSL VPNs.

Table 1 shows traffic for all of the vulnerabilities that featured in June or July, along with their CVSS and EPSS scores. Here we can see the dramatic dip in traffic targeting CVE-2020-8958, which dropped more than 60% from the previous month. It is also worth noting that CVE-2022-42475, the new SSL VPN buffer overflow vulnerability, has a fairly low EPSS score of 46% chance of being malicious exploitation. This might seem low for a critical vulnerability in security infrastructure, but this EPSS score still puts it in the 97% percentile of all vulnerabilities. We will be curious to see if the score changes over time.

| CVE-2020-42475 A heap-based buffer overflow vulnerability in several versions of the Fortinet FortiOS and FortiProxy SSL VPNs. A remote unauthenticated attacker could use this to execute code or commands. NVD |

| CVE Number | July Traffic | Change from June | CVSS v3.x | EPSS Score |

| CVE-2017-9841 | 5181 | 58 | 9.8 | 97.5% |

| CVE-2020-8958 | 3774 | -5811 | 7.2 | 83.1% |

| CVE-2022-24847 | 2781 | 77 | 7.2 | 0.1% |

| CVE-2020-0688 | 2505 | 1171 | 8.8 | 97.2% |

| CVE-2022-42475 | 1859 | 1449 | 9.8 | 46.0% |

| CVE-2019-9082 | 1802 | -22 | 8.8 | 97.5% |

| CVE-2022-41040/CVE-2021-34473 | 1639 | 553 | 9.8 | 97.4% |

| CVE-2021-3129 | 1585 | -90 | 9.8 | 97.5% |

| CVE-2022-22947 | 1404 | -175 | 10 | 97.6% |

| CVE-2013-6397 | 1249 | 42 | NA | 71.4% |

| CVE-2021-28481 | 980 | 23 | 9.8 | 2.3% |

| CVE-2018-10561 | 886 | 579 | 9.8 | 97.5% |

| 2018 JAWS Web Server Vuln | 850 | -170 | NA | N/A |

| CVE-2021-26855 | 664 | -71 | 9.8 | 97.5% |

| CVE-2021-40539 | 514 | 216 | 9.8 | 97.5% |

| CVE-2020-15505 | 468 | -61 | 9.8 | 97.5% |

| CVE-2021-22986 | 418 | 185 | 9.8 | 97.5% |

| CVE-2020-25078 | 353 | -494 | 7.5 | 97.0% |

| NETGEAR-MOZI | 317 | 101 | NA | N/A |

| CVE-2017-18368 | 280 | -96 | 9.8 | 97.6% |

| CVE-2014-2908 | 258 | -3 | NA | 0.6% |

| Citrix XML Buffer Overflow | 255 | -4 | NA | N/A |

| CVE-2021-26084 | 226 | 73 | 9.8 | 97.5% |

| CVE-2021-26086 | 171 | 36 | 5.3 | 94.4% |

| CVE-2019-18935 | 167 | -24 | 9.8 | 90.8% |

| CVE-2017-1000226 | 163 | 45 | 5.3 | 0.1% |

| CVE-2021-27065 | 153 | 100 | 7.8 | 93.4% |

| CVE-2021-44228 | 123 | 39 | 10 | 97.6% |

| CVE-2018-13379 | 110 | -38 | 9.8 | 97.5% |

| CVE-2014-2321 | 84 | 70 | 96.4% | |

| CVE-2019-12725 | 51 | 49 | 9.8 | 96.7% |

| CVE-2022-1388 | 48 | 3 | 97.5% | |

| CVE-2022-22965 | 28 | -2 | 9.8 | 97.5% |

| CVE-2020-3452 | 24 | 7 | 7.5 | 97.6% |

| CVE-2022-40684 | 24 | -77 | 9.8 | 96.7% |

| CVE-2021-21985 | 12 | -9 | 9.8 | 97.5% |

| CVE-2018-20062 | 3 | 0 | 9.8 | 96.8% |

| CVE-2021-41277 | 3 | -2 | 10 | 96.7% |

| CVE-2021-21315 | 2 | 0 | 7.8 | 97.2% |

| CVE-2021-33357 | 2 | 1 | 9.8 | 96.4% |

| CVE-2008-6668 | 1 | 1 | NA | 0.4% |

| CVE-2017-0929 | 1 | 1 | 7.5 | 6.9% |

| CVE-2018-1000600 | 1 | 1 | 8.8 | 95.6% |

| CVE-2018-7600 | 1 | -1 | 9.8 | 97.6% |

| CVE-2019-9670 | 1 | -8 | 9.8 | 97.5% |

| CVE-2020-17496 | 1 | 1 | 9.8 | 97.5% |

| CVE-2020-25213 | 1 | 1 | 9.8 | 97.5% |

| CVE-2020-7796 | 1 | 0 | 9.8 | 74.8% |

| CVE-2021-31589 | 1 | 1 | 6.1 | 0.2% |

| CVE-2008-2052 | 0 | -8 | NA | 0.2% |

| CVE-2018-18775 | 0 | -2 | 6.1 | 0.2% |

| CVE-2020-13167 | 0 | -2 | 9.8 | 97.4% |

| CVE-2021-25369 | 0 | -4 | 6.2 | 0.1% |

| CVE-2021-29203 | 0 | -2 | 9.8 | 96.0% |

| CVE-2021-33564 | 0 | -2 | 9.8 | 6.3% |

Table 1. Traffic volumes, change from the previous month, CVSS and EPSS scores for all vulnerabilities that were targeted in either June or July 2023.

Targeting Trends

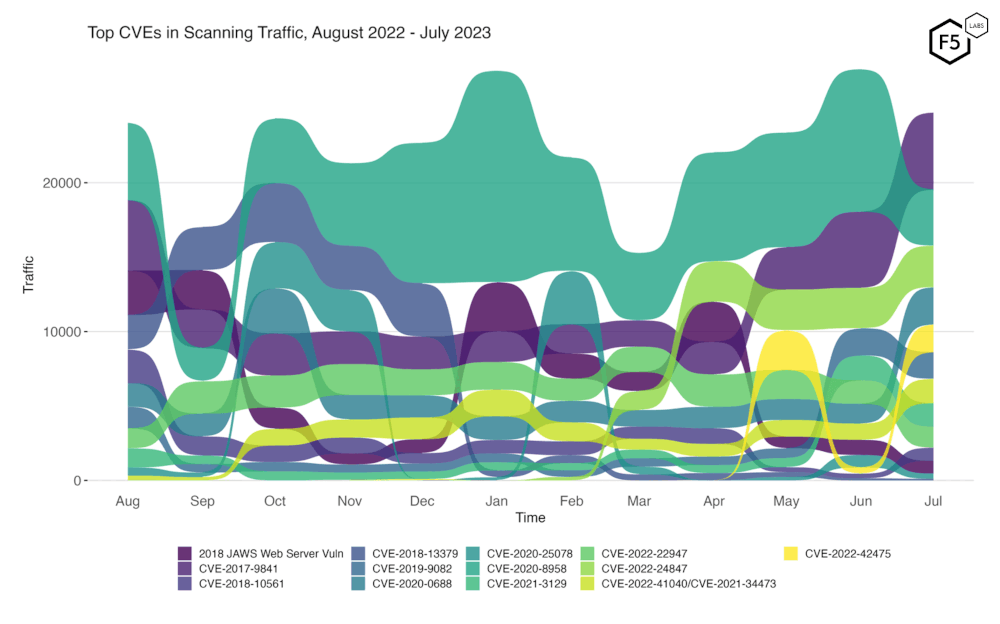

Figure 2 shows the change over the past twelve months in attack volume and rank for 13 of the top vulnerabilities. These 13 collectively constitute the top five from each of the twelve months. In this plot, several things stand out: the light yellow color here is the new SSL VPN vulnerability, and you can see how it spiked in May, only to subside in June before growing again to near its May level in July. CVE-2022-42475 was allocated in 2022 but was published in early January 2023, so it has been public knowledge for seven months by now.

Figure 2. Evolution of vulnerability targeting trends over previous twelve months. This plot shows fourteen vulnerabilities which collectively represent the monthly top five for all twelve months.

Long Term Trends

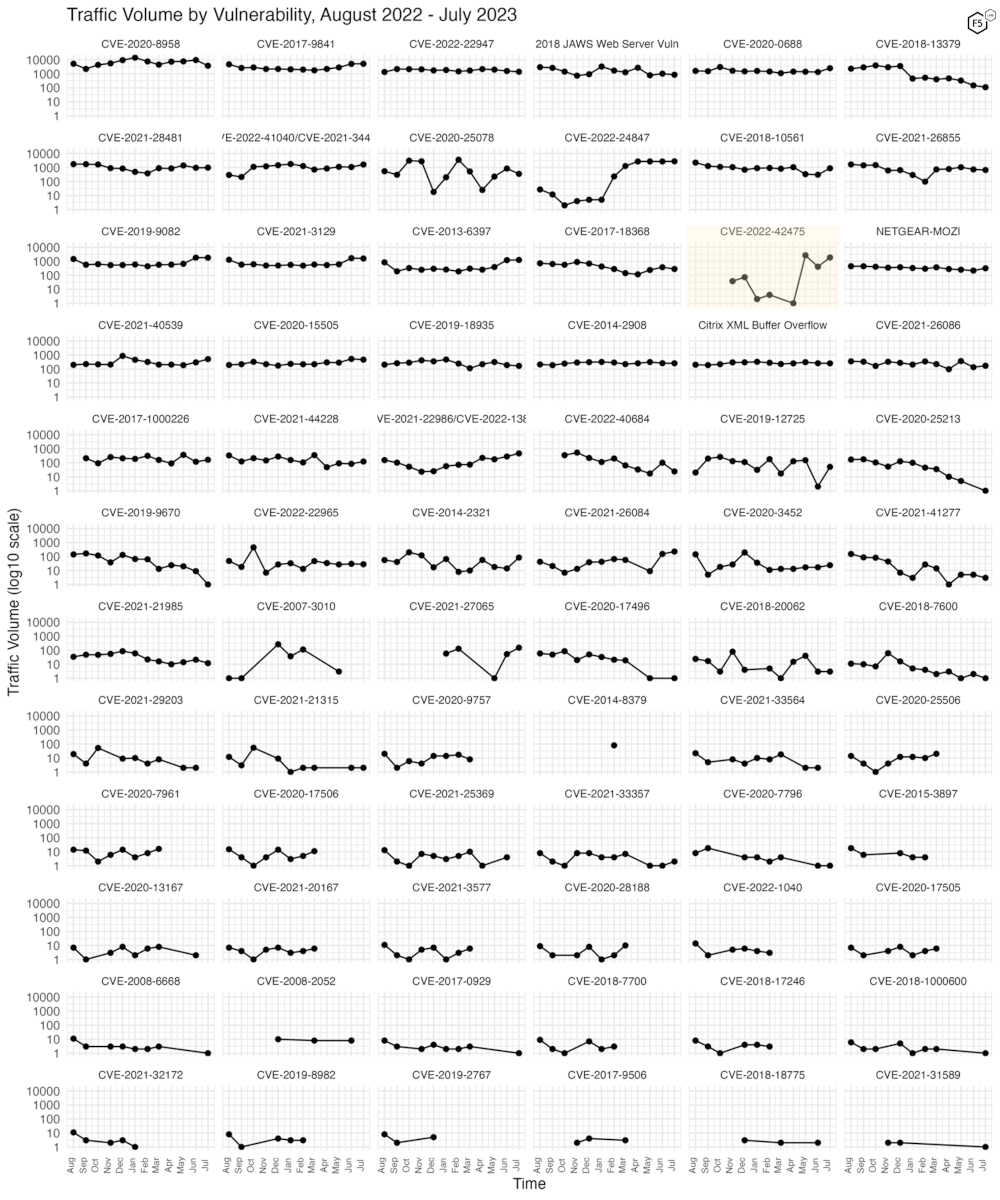

Figure 3 shows the traffic volume over the last 12 months for 72 CVEs that we track. In this view the recent growth of CVE-2022-42475 is apparent, since it grew roughly a thousandfold between April and May 2023. This plot also shows the continuing decline of another Fortinet vulnerability, CVE-2018-13379.

Figure 3. Traffic volume for the last twelve months for 72 tracked CVEs.

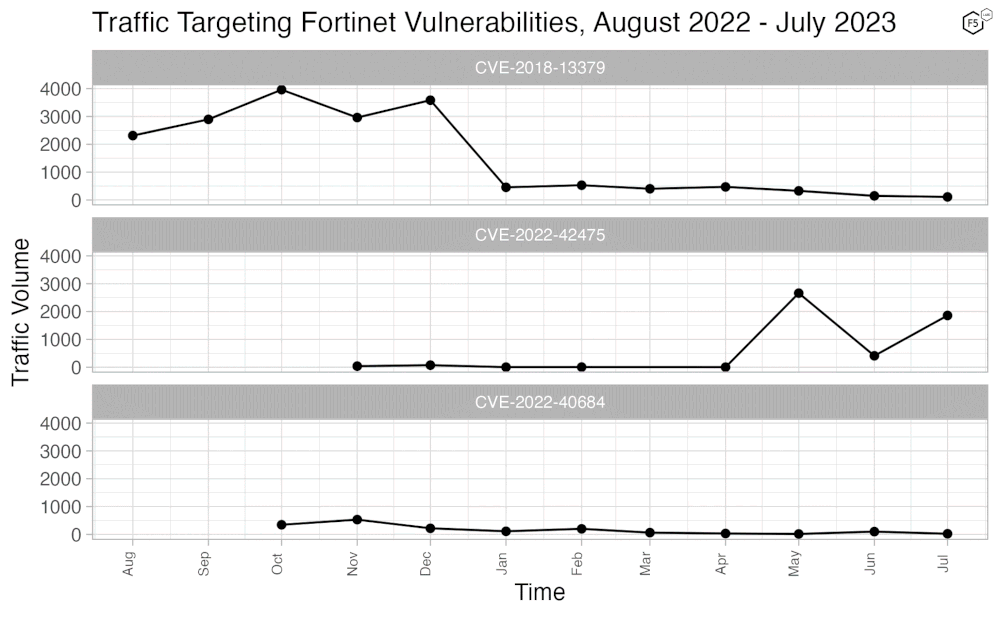

Since recent traffic has shown change in several Fortinet CVEs, we decided to compare them in more detail. Figure 4 shows the traffic over time for three Fortinet vulnerabilities, CVE-2018-13379, CVE-2022-40684, and the most recent, CVE-2022-42475. 13379 is a directory traversal vulnerability that can result in the disclosure of administrator credentials for the VPN, 40684 is an authentication bypass vulnerability affecting many of the same versions, and this latest one, 42475, is a buffer overflow leading to RCE.

Figure 4. Attack traffic targeting recent Fortinet CVEs. Attacker interest in the two older vulnerabilities (CVE-2018-13379 and CVE-2022-40684) had already subsided before attack traffic against CVE-2022-42475 picked up.

Figure 4 shows that attacker interest in the other two Fortinet vulnerabilities dropped months before CVE-2022-42475 was released, probably because most affected versions were patched. Nevertheless it is interesting to see this continued interest in remote access infrastructure. We will be on the lookout for other exploit attempts against Fortinet vulnerabilities in the future.

Conclusions

One thing that is consistently apparent in the SIS data is the mutability of attacker interest. This is not the first time CVE-2020-8958 has dropped dramatically, and in the past it has always rebounded, which was partly why we have assessed this traffic to indicate interest in building DDoS infrastructure. (The other reason is that gigabit-capable fiberoptic routers such as the one that CVE-2020-8958 applies to are perfect for DDoS because of their prodigious throughput capability.) We will be curious to see how this evolves over the next few months. In the meantime, we have some demonstrated interest in Fortinet products after some quiet time on that front—we will dig into this and see if we can unearth any more interesting intelligence about SSL VPNs or remote infrastructure targeting. See you next month!

Recommendations

- Scan your environment for vulnerabilities aggressively.

- Patch high-priority vulnerabilities (defined however suits you) as soon as feasible.

- Engage a DDoS mitigation service to prevent the impact of DDoS on your organization.

- Use a WAF or similar tool to detect and stop web exploits.

- Monitor anomalous outbound traffic to detect devices in your environment that are participating in DDoS attacks.