Introduction

Phishing has proved so successful that it is now the number one attack vector.1 The Anti-Phishing Working Group reports that in the first half of 2017 alone, more than 291,000 unique phishing websites were detected, over 592,000 unique phishing email campaigns were reported, and more than 108,000 domain names were used in attacks.2 In 2016, the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) received phishing reports from more than 19,000 victims.3 However, IC3 also notes that only an estimated 15% of victims ever report crimes to law enforcement, so the actual total could exceed 125,000. Of the 19,000 reported cases, the total cost exceeded $31 million.

In this report, we explore why phishing campaigns work so well, how unsuspecting users play into the hands of attackers, and what organizations can do about it.

How Phishers Bait Their Hooks with Information You Volunteer

Seven minutes until his next meeting, Charles Clutterbuck, the CFO of Boring Aeroplanes, had just enough time to answer a few emails. He flopped onto his padded leather chair and tapped out his password. A dozen emails glowed unread at the top of his inbox stack. He skimmed down the list of names and subjects when one caught his eye. It was from an old friend. With a nod, he clicked it up. “How’s it going, Clutt?” the email began. He smiled at the old nickname from the dorm days when he first met Bill. Funny that Bill was emailing him at his work address, but that question was quickly forgotten as he skimmed the message.

From: Bill Fescue b.fescue@blafmail.com

Sent: Thursday, July 6, 2017 12:16

To: Charles Clutterbuck c.clutterbuck@boringaeroplanes.com

Subject: My new hoss

How’s it going, Clutt?

Hit the track with my new Falkens and, guess what? Tremendous grip! No more wheel spins. Check out my track time and cornering: http://vizodsite.com/istruper_video_10

See you at next week’s Autocross?

Bill

As you might have guessed, this is a spear phishing email.

Download the full report now!

In spear phishing, the attacker leverages gathered information to create a specific request to trick someone into running something or giving up personal information. It’s an extremely successful technique and attackers know this. In fact, the Anti-Phishing Working Group reports that phishing has gone up 5,753% over the past 12 years.4

Phishers work by impersonating someone trusted by the target, which requires crafting a message that is credible and easily acceptable. To do this, the phisher needs information about the target to construct their disguise and bait the hook. They get this information by research and reconnaissance.

In the example above, an executive at a military plane parts supplier received an email apparently from a friend. His interest in car racing—as well as his friend’s name and style of speaking—was plucked off social media. The attacker spent a few minutes of web research on car racing to get the vernacular right and then created an email account in the friend’s name. The link is to a site with a video server that sends an exploit geared to the target’s laptop operating system (gleaned from research on the company infrastructure). It loads specialized malware built to exfiltrate aerospace intellectual property. Easy, peasy.

So, we know that attackers are gathering information from social networks and various Internet sources, but just how much information is available? Defenders spend quite a bit of energy preventing the obvious information leaks like passwords, crypto keys, and personally identifiable information (PII). Those are high impact information leaks, but what about the low impact ones?

It’s worth exploring what’s typically discovered in an attacker’s passive electronic reconnaissance. And, that’s not counting active recon like calling the company’s main phone number and trying to extract information via pretexting5 or going onsite for dumpster diving.6 This is all low-risk stuff that can happen in secret from afar. But, as the Great Detective said, “You know my method. It is founded upon the observation of trifles.”7

How Attackers Collect Data About Your Employees

We’ve seen an everyday example of how easily a competent corporate executive (or any other employee, for that matter) can be drawn into a phishing scam through social engineering. Now let’s look at how some of the seemingly innocent actions we take (information we post) on the Internet make the job of a phisher simple—like taking candy from a baby.

Since spear phishers go after a specific organization, they need to know who works there before they can begin their targeting. A lot of people tag themselves on various social media sites as an employee of a particular company. LinkedIn is a site that provides lots of details on where people work. Quora is another site where tech people congregate:

Through these sites, it’s not hard for phishers to gather up a list of names of employees at a specific organization.

Social Media and Personal Information

Despite the security team’s best efforts to prevent it, employees will share and spread information about themselves all over the Internet. Social media companies expend tremendous effort to encourage people to join and post information about themselves. Some valuable bits of information that attackers can use are:

- Work history

- Education information (college and high school attended)

- Family and relationship information

- Comments on links

- Dates of important life events

- Places visited

- Favorite sites, movies, TV shows, books, quotes, etc.

- Photographs

Profiling

All these pieces of information provide powerful leverage points for attackers, but they also provide a lot of valuable indirect information. As our phishing example points out, attackers can observe the writing style of the people they want to impersonate. Beyond that, they can also create detailed psychological profiles of victims. There are a number of tools and techniques available to do things like:

- Analyze sentiment to determine people’s opinions and political leanings8

- Analyze posting times to determine when people are awake (and asleep) and what their home time zones are18

- Determine an individual’s personality type, which can inform manipulation techniques19

- Analyze relationships and friendship ties20

With sites like Facebook that host nearly 2 billion users,9 it’s very easy to craft a Google search for someone with “[name] [location] site:facebook.com” to find their page.

Many social media users are part of interest groups, which can provide useful leverage points for a phisher.

Even when someone sets their social media profile to “private,” it’s still not too difficult for an attacker to break in and get what they want. Here is a hacking service being advertised on a Darknet for just that purpose:

People Search Engines

In addition to social media sites, there are numerous “people search” sites like Pipl, Spokeo, and ZabaSearch. Many of these sites pull together profiles based on dozens of resources. Sometimes they’re not very helpful, like this example for me, because I’m a paranoid security guy:

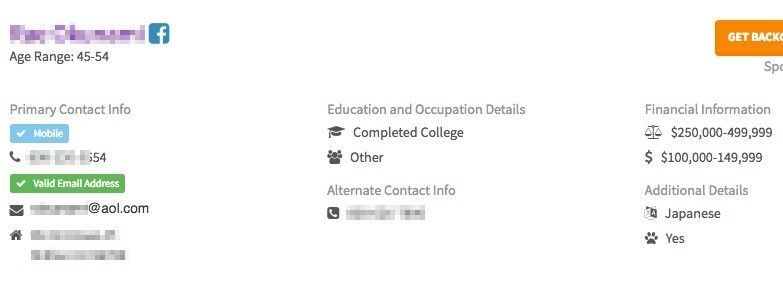

However, different sites can dig up some interesting data, like this example:

Note how this site provides Facebook information, email address, annual income, education, phone number, age range, and even racial profiling. Here’s some typical information you can get from these kinds of sites:

- Home address

- Mobile phone number

- Home (landline) phone number

- Age

- Salary range

- Spouse and family

- Email address, which leads to possible usernames

- Middle name

- Maiden name

Most employees don’t think about things like this—because most employees don’t think like bad guys. It doesn’t occur to them how much personal and work-related information they are freely volunteering on various websites—or how easy they make it for phishers to pull information together into some pretty comprehensive professional dossiers. The lesson here is think before you volunteer information about yourself and your work, and limit the number of websites where you do this.

How Attackers Gather Data about Your Organization

When attackers want to go after a specific organization but need to know which individuals within that organization to target, then they need to dig through corporate and business records. They can start simply with the ownership records, which are freely available over the web, as in this example:

Publicly traded companies have even more information available online from their SEC filings. Here is an excerpt from a recent 8-K filing from F5 about our new corporate headquarters:

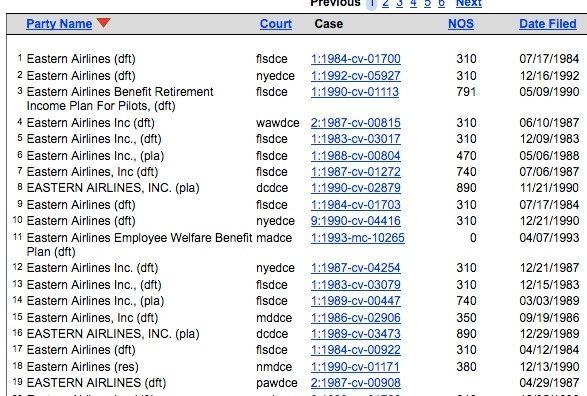

Many corporations that have been around for more than a few years have probably been involved in a lawsuit or three. Attackers can pull those records, as well, like this example from now defunct Eastern Airlines:

Like the people search databases we saw earlier, there are also aggregator search tools for corporations, such as OpenCorporates, that pull together a lot of this information into a single place.

These sources can help attackers build profiles of individuals and department names, which are powerful tools for flavoring their phishing bait. Scanning a company’s website can also give you clues about business partners and affiliates, for which you can repeat all of these searches.

Your Organization’s Internet Presence

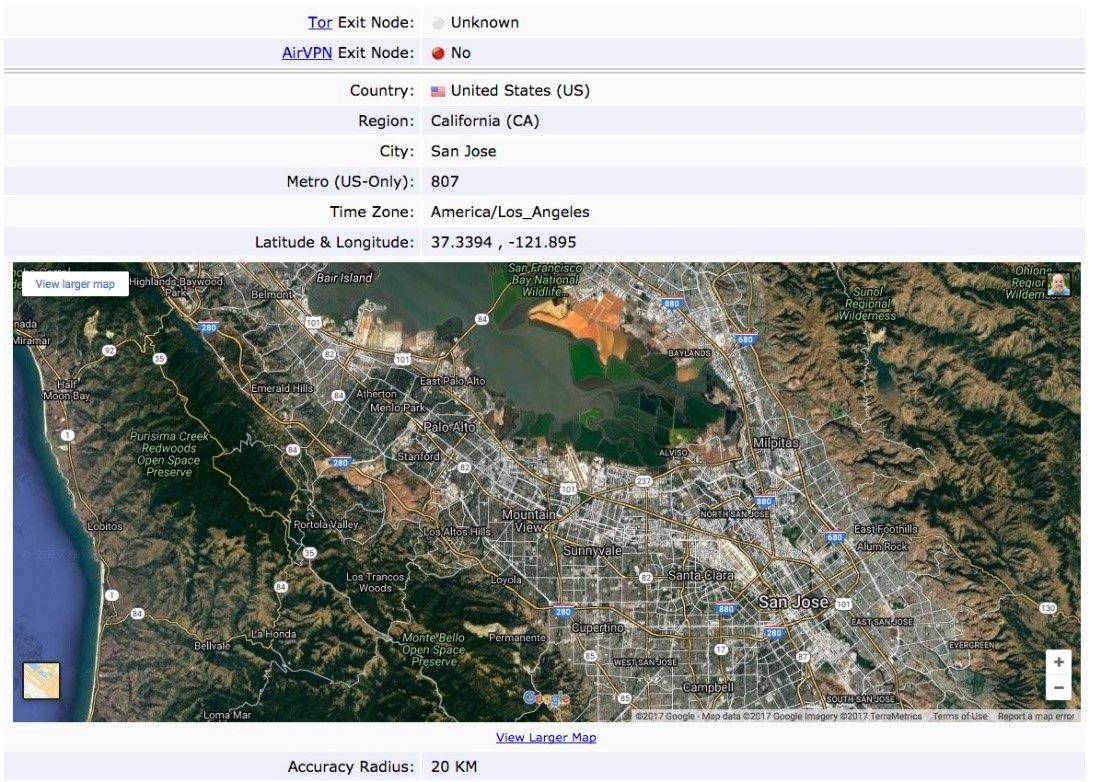

Everyone active on the Internet has an IP address, and IP addresses can provide some basic information about where they terminate and who owns them.

Granted, some of this information can be misleading because IP addresses can trace back to the ISP rather than the actual organization. But, sometimes attackers get lucky. Most of the time, they can uncover where sites are being hosted and gain some basic information about the company’s network configuration.

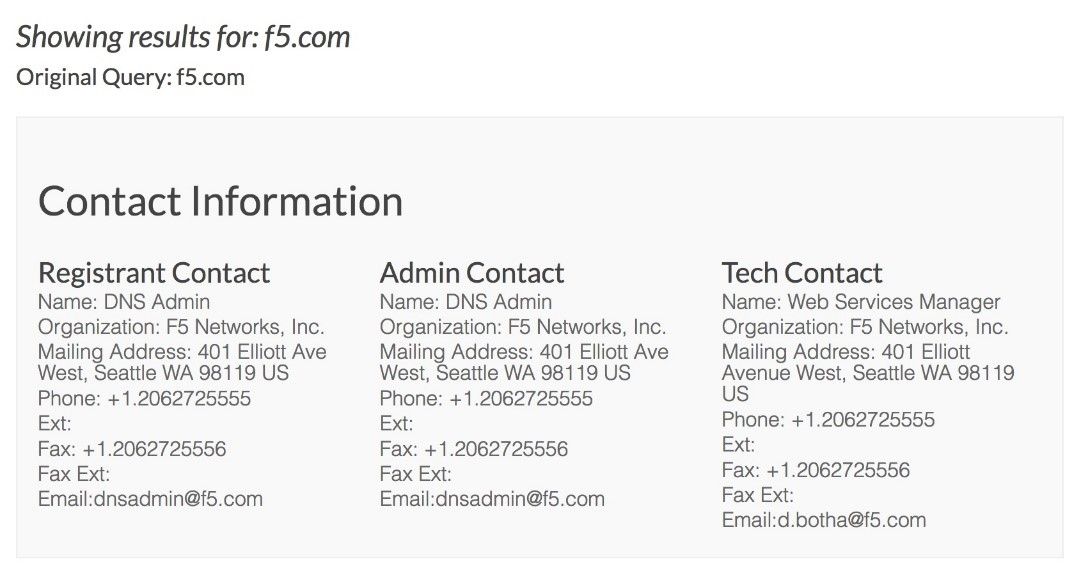

In addition to the IP address information, every organization with a domain has domain registration information. Like IP information, for most sizable organizations, it’s going be generic and not reveal much that’s useful. But again, sometimes attackers get lucky.

Corporate Email Addresses

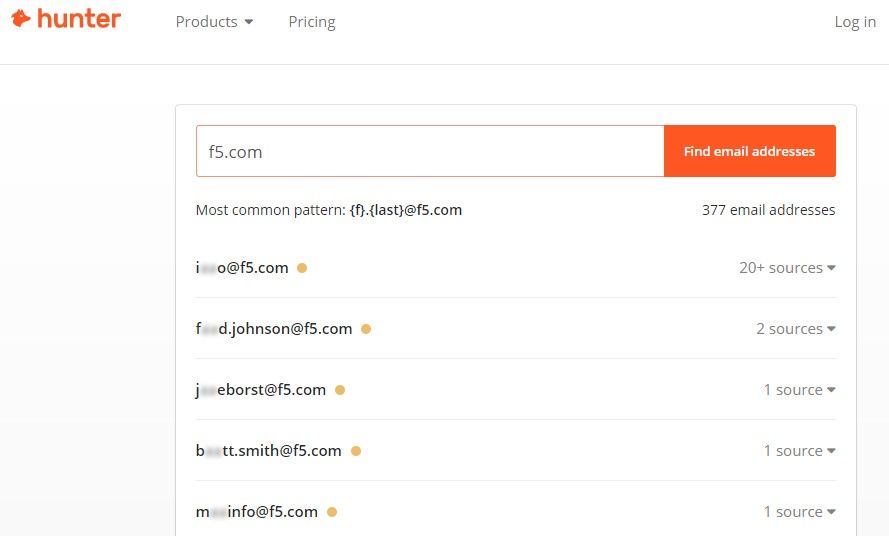

Where else can attackers find usable email addresses for an organization? There are many companies out there that can help with that. Here’s Hunter,10 which not only provides email addresses but also provides hints on the email format used.

Beware of Data Leaking Out of Your Equipment

To pull off successful phishing scams, at a minimum, attackers need information about your organization and your employees. We’ve already seen several ways they go about getting this information. But one area organizations often overlook is the information that’s leaking out of their systems.

Improperly configured network systems and applications can leak internal configuration and infrastructure information. This can include information like server names, private network addresses, email addresses, and even usernames. Devices and software that have been known in the past to leak internal data onto the Internet include DNS servers, self-signed certificates, email headers, web servers,11 web cookies, and web applications.12

Here is a simple example of how a sloppily configured web server can reveal the internal IP addressing scheme:

HTTP/1.0 200 OK

Date: Mon May 22 15:31:46 PDT 2017

Server: Macrohard-YYZ/6.0

Connection: Keep-Alive

Content-Type: text/html

X-Powered-By: BTQ.NET

Accept-Range: bytes

Last-Modified: Sat, May 20 04:14:01 PDT 2017

Content-Length: 1433

Connection-Location: http://192.168.0.10/index.htm

Attackers can also comb through web application source code to look for developer names, internal code words, and even references to supposedly hidden services.13 Almost all of these kinds of technical information leakages are rated very low impact and are usually deprioritized in remediation.

Application Platform Discovery

Applications are rarely built from scratch but are instead assembled from libraries and existing frameworks. All of these application components can contain vulnerabilities as well as clues to the development team and processes in an organization. There are numerous easy-to-use tools that can uncover what is being deployed. Here is the BuiltWith tool’s analysis of a site:

Email Headers

An excellent source of internal configuration information can be gleaned from email headers. Attackers can simply fire off a few email inquiries to folks at an organization and see what they can find. Here’s a typical email header using our example company, Boring Aeroplanes, from our phishing example. Note both internal and external IP addresses ae shown, along with server names:

Received: from edgeri.boringaeroplanes.com (host-12-154-167-196.boringaeroplanes.com. [312.154.167.296])

Received-SPF: pass (google.com: domain of charles.clutterbuck@boringaeroplanes.com

designates 312.154.167.296 as permitted sender) client-ip=312.154.167.296;

Received: from edgeri.boringaeroplanes.com (172.31.1.48) by

WEXCRIB00001059.corp.internal.boringaeroplanes.com (172.31.1.42) with Microsoft

SMTP Server id 14.3.301.0; Fri, 28 Apr 2017 10:40:36 -0400

Received: from WEXCRIB00001065.corp.internal.boringaeroplanes.com (70.338.297.31)

by WEXCRIB00001059.corp.internal.boringaeroplanes.com (172.31.1.42) with

Microsoft SMTP Server (TLS) id 14.3.301.0; Fri, 28 Apr 2017 10:39:23 -0400

Received: from WEXCRIB00001054.corp.internal.boringaeroplanes.com

([169.254.9.522]) by WEXCRIB00001065.corp.internal.boringaeroplanes.com

([70.338.297.31]) with mapi id 14.03.0301.000; Fri, 28 Apr 2017 10:39:31 -0400

From: "Clutterbuck, Chuck" <charles.clutterbuck@boringaeroplanes.com>

Subject: Inquiry

Thread-Topic: Inquiry

Thread-Index: AdLAKumC2+2KaqenReOr0muBBLJpfQ==

Date: Fri, 28 Apr 2017 14:39:30 +0000

Accept-Language: en-US

x-originating-ip: [10.16.15.170]

x-keywords4: SentInternet

x-cfgdisclaimer: Processed

MIME-Version: 1.0

Return-Path: charles.clutterbuck@boringaeroplanes.com

From this, attackers have a number of IP addresses, and they know what software the mail server is running and how email flows out of the organization.

How Attackers Pull it all Together, and How You Can Fight Back

By now, it should be pretty evident why phishing scams are becoming so rampant. Information about individuals and corporations is readily available and easy to find on the Internet, making it easy for attackers to pull phishing schemes together—and with great success.

None of the bits of information we discussed in previous sections is particularly dangerous by itself, so most people are not concerned. However, one of the principal tenets of information theory is that each piece of information becomes more valuable as you find more related pieces of information. One bit of low impact information is slightly useful. Two bits of related information makes both more useful. Add three, five, or ten pieces and the value can become inestimable.

What Does a Phisher Need?

Let’s walk through how an attacker can use specific information about individuals and corporations to build a phishing scam. Their first, key objective is to zero in on the correct person within the organization to accept the phishing “hook.” This means finding the names of persons through organizational data research. The attacker’s goal is to identify the people in key positions who have access to the data to be hacked. Barring that, attackers try to find the people who know the people in key positions so they can work their way through the inside network toward the goal. If that doesn’t work, an attacker can also go after individuals at trusted partner or supplier companies, leveraging their relationships and access to find a way in.

Once an attacker identifies the specific individuals, they can psychologically profile them based on their social media postings and affiliations. (In some cases, instead of phishing, an attacker might look for websites that the victim frequents and compromise those sites to plant drive-by downloads.17 This is called a Watering Hole Attack.)14

For crafting a phishing email, an attacker can use all the social media postings and organizational information to create the lure. They can go directly at an individual’s interests and friends, like in the example given above. They can also go indirectly and use organizational information and spoof the company’s HR department to ask employees to verify basic information.15 Knowing which individuals to impersonate in HR can help solidify the phishing email.

The attack doesn’t end there. The cyber crook wants to break into the network and probably plant malware to steal data. To make sure the malware works properly, they customize it for the appropriate versions of software running internally and the IP networks in use. In the example used in the beginning of this report, the attacker sent an exploit specifically tailored for the version of software running on the victim’s machine. Sneaking stolen data back out, called exfiltration, is always a challenge, but knowing what internal servers there are and where they’re located can provide an easy roadmap.

What to Do

There’s a limit to what we as security professionals can do to keep people from sharing information on social media. In government agencies, there are more restrictions and education around this kind of behavior (called operational security).16 In the private and commercial world, corralling such behavior is much harder. So, security awareness training, citing these examples, is a good place to start. At least users will be aware of the consequences of their sharing and be forewarned to the deviousness of the attacks. Users should also be urged to report any suspicious emails and verify with IT or Security before running outside software or providing their login credentials.

A good resource you can offer your users is this advice from Public Intelligence on how to reduce their online exposure by “opting out.”17 The fewer bits of data attackers can latch onto, the better.

It is a good idea for your security team (or better yet, your threat intelligence team) to periodically scan your own organization or hire a penetration tester. This could give you clues as to who and where attackers will strike first.

Closing the information leakage on your Internet-facing gear is often not hard to do and is recommended. Every door you close denies an attacker another puzzle piece of information. All domain and IP registries should be set up with generic role names and identifiers instead of the names of individuals. Most IT folks do this anyway to reduce potential spam, but it doesn’t hurt to check.

Lastly, contracting with a good penetration testing firm to do reconnaissance and a social engineering test is a great way to see what you might have missed. It’s better to pay and control the results of a mock attack than have to live through a real one.