Introduction

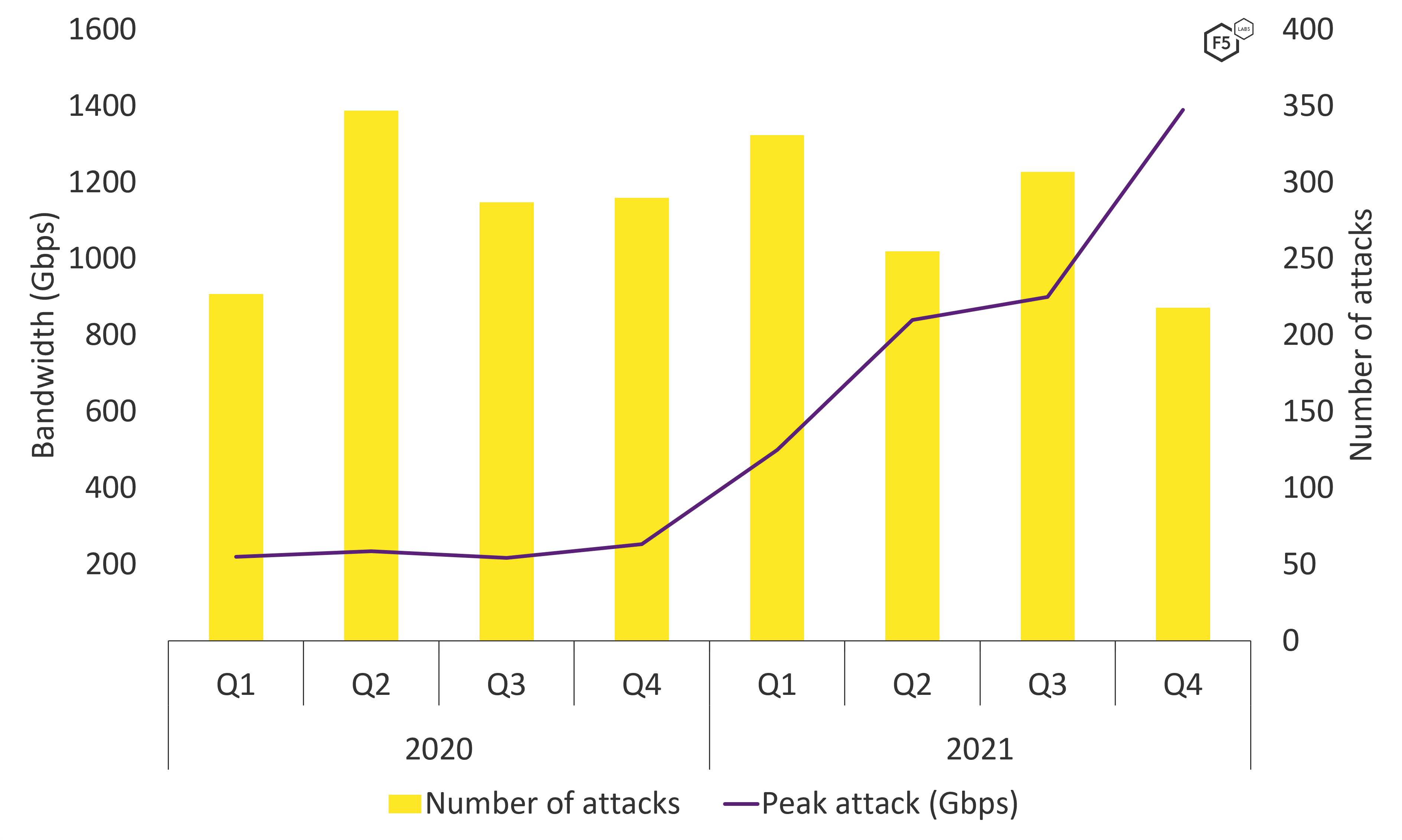

Distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks in 2021 showed some fascinating developments. Analysis of attack data collected by F5’s Silverline team, which provides managed DDoS protection services, among others, revealed some interesting trends: the overall number of DDoS attacks declined marginally compared with 2020, while the size and complexity of those attacks grew significantly (see Figure 1). Attacks targeting SSH, often used by attackers to build out new botnets for DDoS attacks, have declined slowly but steadily. Meanwhile, vulnerabilities in consumer devices, such as routers, were rapidly exploited to join them to these botnets. Reports, such as Europol’s Internet Organized Crime Threat Assessment (IOCTA), highlight that threat actors are increasingly using DDoS attacks to pressure victims into paying ransomware attack demands. Groups known to use this method include Avaddon, DarkSide, Ragnar Locker and Sodinokibi.1 Even organized cybercriminals recognize the threat of DDoS attacks. The IOCTA also reported that administrators of online illegal marketplaces have improved their own defenses to defend against DDoS attacks from competitors.

Executive Summary

- Silverline mitigated its largest-ever DDoS attack, which peaked at just under 1.4 Tbps, almost 5.5 times larger than the largest attack in 2020.

- The overall number of DDoS attacks declined 3% between 2020 and 2021.

- Small to medium-size DDoS attacks (up to 250 Gbps) declined by 5%.

- DDoS attacks larger than 250 Gbps grew by 1,300%.

- Finance, the target of over 25% of all attacks, became the most attacked sector in 2021.

- Volumetric (network flood) DDoS attacks are still the most prevalent, accounting for 59% of all attacks.

- Protocol and application DDoS attacks both grew in 2021 by 2% and 5%, respectively.

- TCP DDoS attacks almost doubled in 2021 compared with 2020 and accounted for 27% of all attacks.

Mapping the ATT&CKs

Our recent reports have made increasing use of the MITRE ATT&CK framework in an attempt to present findings and conclusions in a way that is consistent within our own body of work and that also allows for simple comparisons with other research.2 To this end, this report will include ATT&CK technique IDs to allow for easy cross-referencing. Table 1 shows the mapping between DDoS terminology and ATT&CK techniques.

| F5 DDoS category | ATT&CK technique | Purpose of attack | ATT&CK sub-technique | Examples |

| Volumetric | Network Denial of Service T1498 | Consume network bandwidth | Direct Network Flood T1498.001 | TCP flood UDP flood ICMP flood |

| Reflection Amplification T1498.002 | DNS reflection NTP reflection memcache reflection | |||

| Protocol | Endpoint Denial of Service T1499 | Overwhelm network device | OS Exhaustion Flood T1499.001 | SYN floods ACK floods |

| Application | Endpoint Denial of Service T1499 | Consume application resources | Service Exhaustion Flood T1499.002 | HTTP flood Slowloris TLS renegotiation |

| Application Exhaustion Flood T1499.003 | Heavy URL Intensive SQL queries | |||

| Application or System Exploitation T1499.004 | Exploit a vulnerability to crash a system or service |

Table 1. Mapping DDoS terminology to MITRE ATT&CK techniques.

2021 DDoS Attacks by the Numbers

We analyzed the raw attack data from the Silverline teams to see how attacks had changed in size, complexity, and frequency compared with 2020.

Attacks Are Getting Larger

DDoS attacks showed a marked decline from the start of 2021 through the end of the year, though the attack frequency remained somewhat consistent for the past two years with 2021 seeing only 3% fewer than 2020. But while Figure 2 shows an overall decline in attack frequency during 2021, it also shows that attack sizes have grown considerably. While peak attack sizes remained consistent throughout 2020, at around 200 Mbps, things changed in February 2021, when the F5 Silverline team detected and mitigated the largest attack it had ever seen, weighing in at 500 Mbps. This record did not last long, however, as 2021 saw larger and larger attacks, culminating with the 1.4 Tbps attack in November. As well as peak attack sizes, the average attack size has also grown. The mean attack size in Q1 2020 was 5 Gbps and over 21 Gbps in Q4 of 2021.

Figure 2. While DDoS attack counts dwindled slightly in 2021, attack sizes grew exponentially.

Figure 3 shows the frequency of DDOS attacks by size, with 100 Mbps or lower being the most common. We might have expected a uniform drop in frequency by size, but Figure 3 also shows that attacks ranging from 1 to 3 Gbps are extremely popular, more so than smaller attacks. Similarly, attacks between 10 and 30 Gbps are more common than those between 6 and 10 Gbps. This is consistent with the findings in our DDoS Attack Trends from 2020, which shows a similar trend.

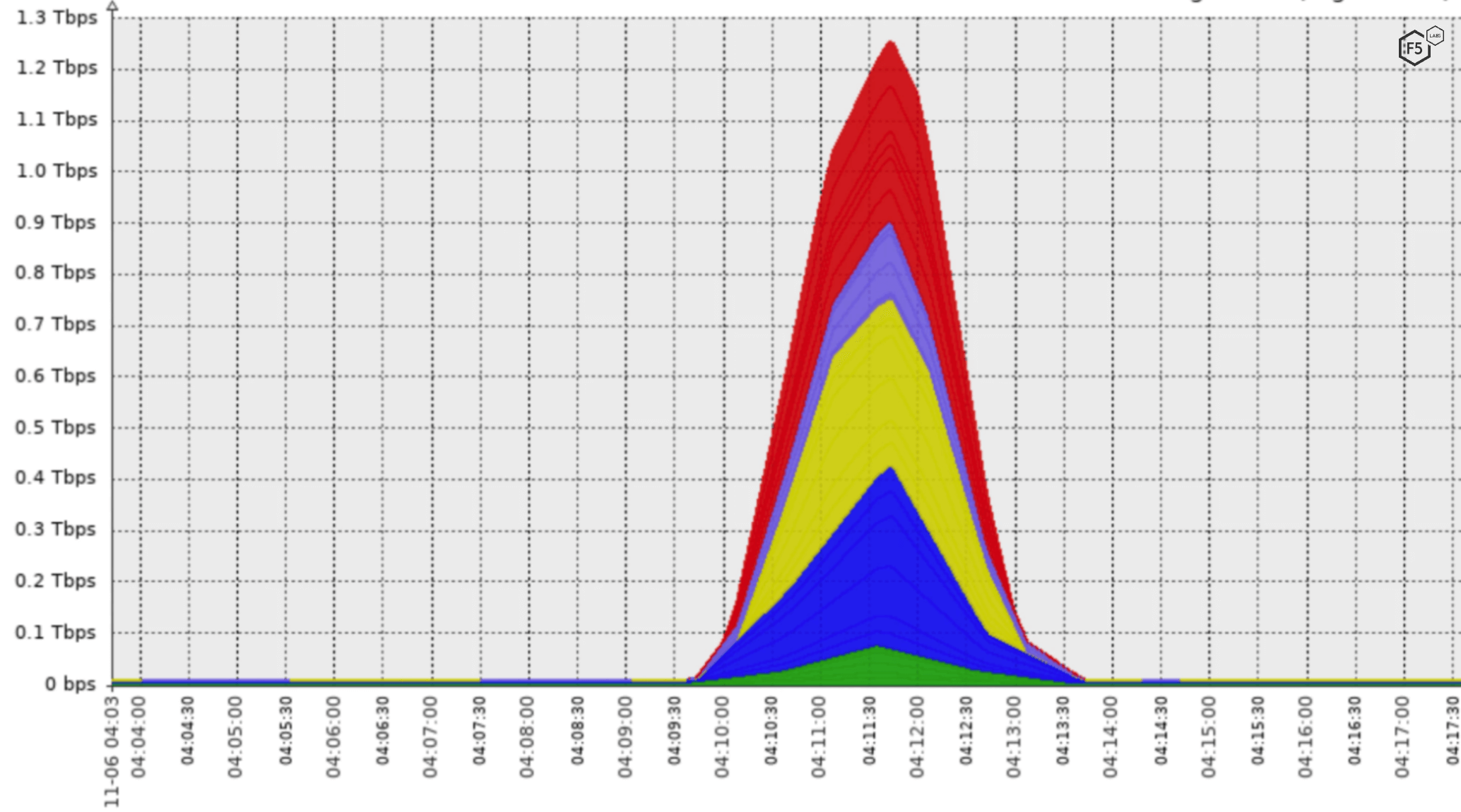

Silverline Defends Against Largest-Ever Attack

In November 2021, Silverline observed and mitigated the largest attack it had ever seen (see Figure 4). The onslaught, targeting an ISP/hosting customer, lasted just four minutes and reached its maximum attack bandwidth of almost 1.4 Tbps in only 1.5 minutes.

Figure 4. Graph of DDoS attack traffic from Silverline showing the November 2021 1.4 Tbps attack.

The attack used a combination of volumetric (DNS reflection) and application-layer (HTTPS GET floods) methods. Interestingly, the huge amount of network traffic, generated by a reflected DNS amplification attack, dwarfed the 100 Mbps of network traffic created by the HTTPS GET flood. This does not make the application-layer attack less serious. The goal of an application-layer DDoS attack is not to consume network bandwidth but to overwhelm the application server, so while 100 Mbps of traffic seems tiny compared to the flood of DNS responses, the resources and queries being requested by the HTTPS attack traffic could have easily consumed a web or database server.

The onslaught lasted just four minutes and reached its maximum attack bandwidth of almost 1.4 Tbps in only 1.5 minutes.

The geographic location of attacking IP addresses, or target IP addresses, is largely irrelevant today. Attackers happily compromise vulnerable devices wherever they are located in the world, and defenders like Silverline have scrubbing centers in all major continents to distribute the attack loads. That being said, it is interesting to observe that the majority of attack traffic was handled by Silverline scrubbing centers in Singapore, the U.S. East Coast, and Germany, suggesting that the majority of attacking devices were located in Asia (see Table 2).

| Percentage of attack seen | |

| Singapore | 29% |

| U.S. East Coast | 27% |

| Germany | 26% |

| United Kingdom | 12% |

| U.S. West Coast | 6% |

Table 2. Proportion of attacks by location seen by Silverline scrubbing centers.

Complex Attacks Are Increasing

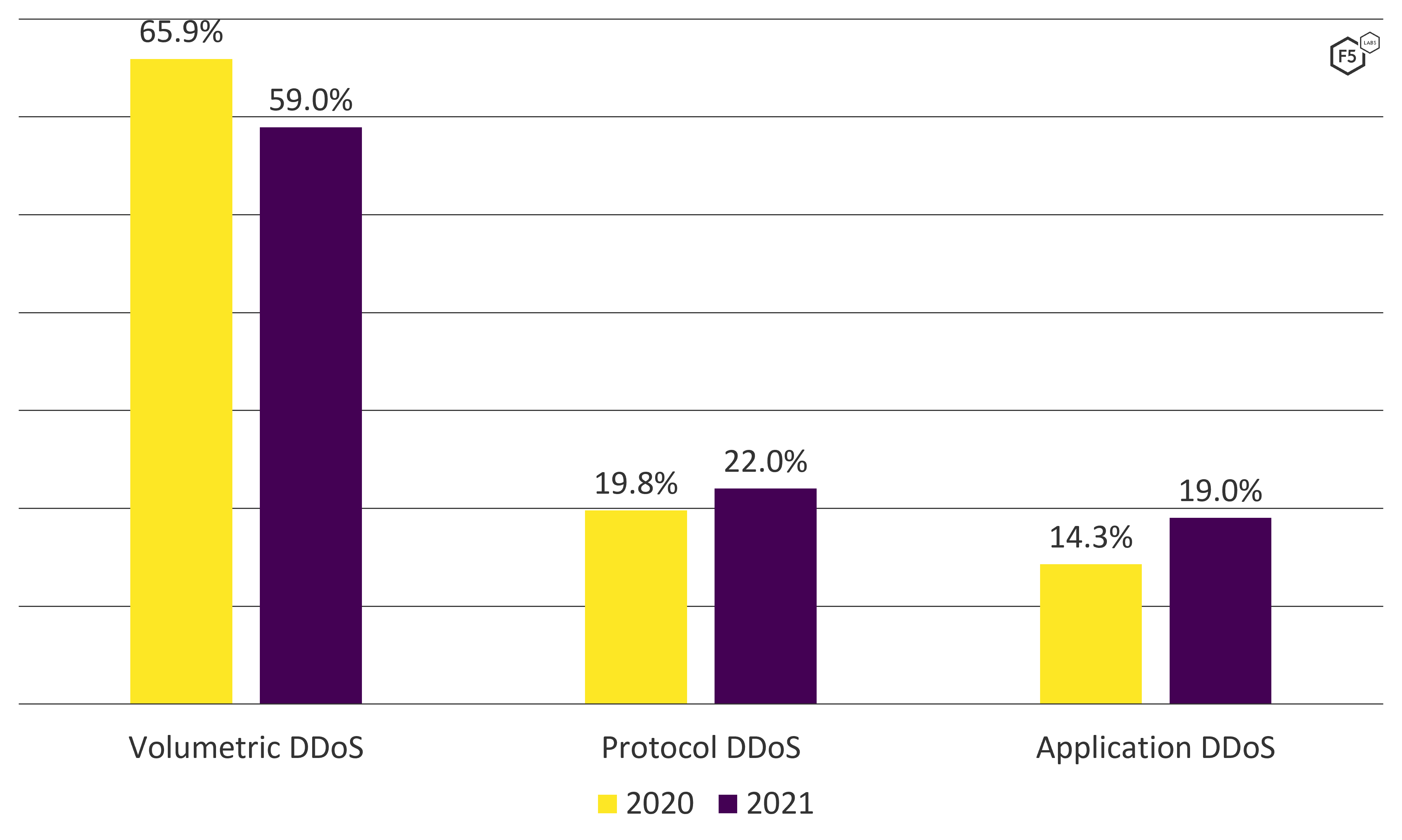

Throughout 2021, the most prevalent form of DDoS attack continued to be volumetric, or the Direct Network Flood T1498.001 technique, to use ATT&CK lexicon. Volumetric attacks are simple and effective, requiring no vulnerability, compromised third-party system, or advanced expertise. Publicly available DDoS tools or services (known as stressers) can launch an attack that sends more traffic to the victim than their network bandwidth can cope with. Combined with UDP reflection attacks, which mask the attackers’ real IP addresses, volumetric denial of service will continue to be the go-to DDoS attack for many threat actors.

But while volumetric attacks continue to dominate DDoS figures, Figure 5 shows that 2021 did see a slight shift toward protocol- and application-type attacks. While volumetric attacks are generally trivial to mitigate, protocol and application attacks can be significantly more challenging, since they can appear as genuine application traffic. Application DDoS attacks saw the biggest change, with a growth of almost 5% compared with 2020).

Figure 5. Graph comparing the distribution of volumetric, protocol, and application DDoS attacks between 2020 and 2021.

In 2021, we saw a significant shift in the protocols used for DDoS attacks. UDP has long been the favored transport protocol of choice for attackers, since it is stateless, allowing threat actors to hide their real IP address and perform reflection attacks. In 2020, 83% of all attacks were UDP-based, with only 17% of attacks using TCP. This changed considerably in 2021, with TCP being used for 27% of attacks. This correlates with more complex protocol and application DDoS attacks (Endpoint Denial of Service T1499), which often need the stateful TCP protocol.

In 2021, 27% of DDoS attacks used TCP, 10% more than 2020.

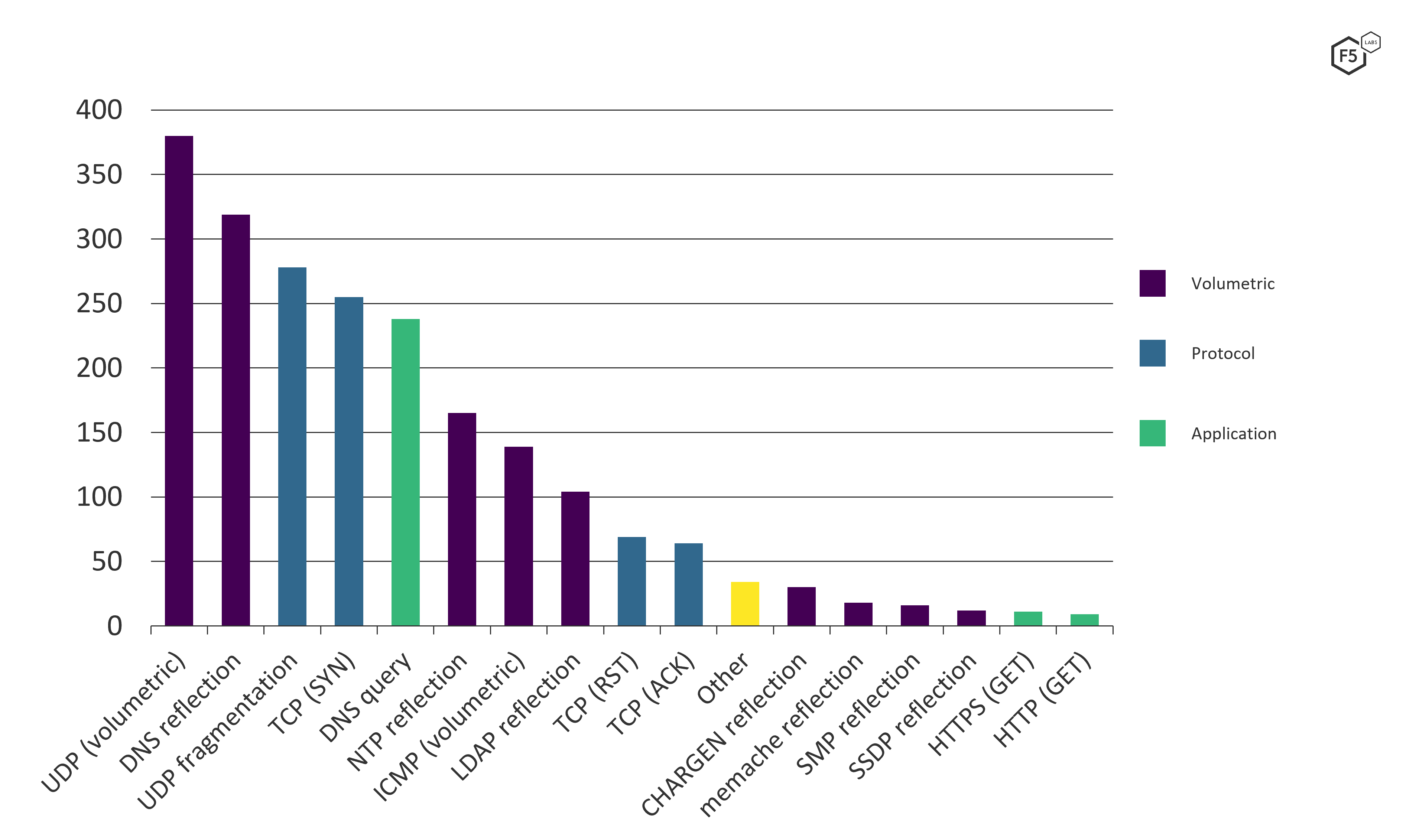

Diving deeper into the data, we find that simple UDP (nonreflection) attacks were the most common DDoS method used in 2021 (see Figure 6). However, despite volumetric attacks accounting for 59% of all attacks, the third, fourth, and fifth most common attack types were protocol- and application-based.

Figure 6. Graph showing frequency of DDoS attack types in 2021.

HTTP(S) denial-of-service techniques are the least common form of DDoS attack but, curiously, this method was used in the largest 1.4 Tbps attack, as described earlier. This record-setting onslaught used a combination of DNS reflection and HTTPS GETS, suggesting the attackers were targeting as many points in the application stack as possible: DNS reflection to consume the network bandwidth and HTTPS GETS as an attempt to overwhelm the application servers.

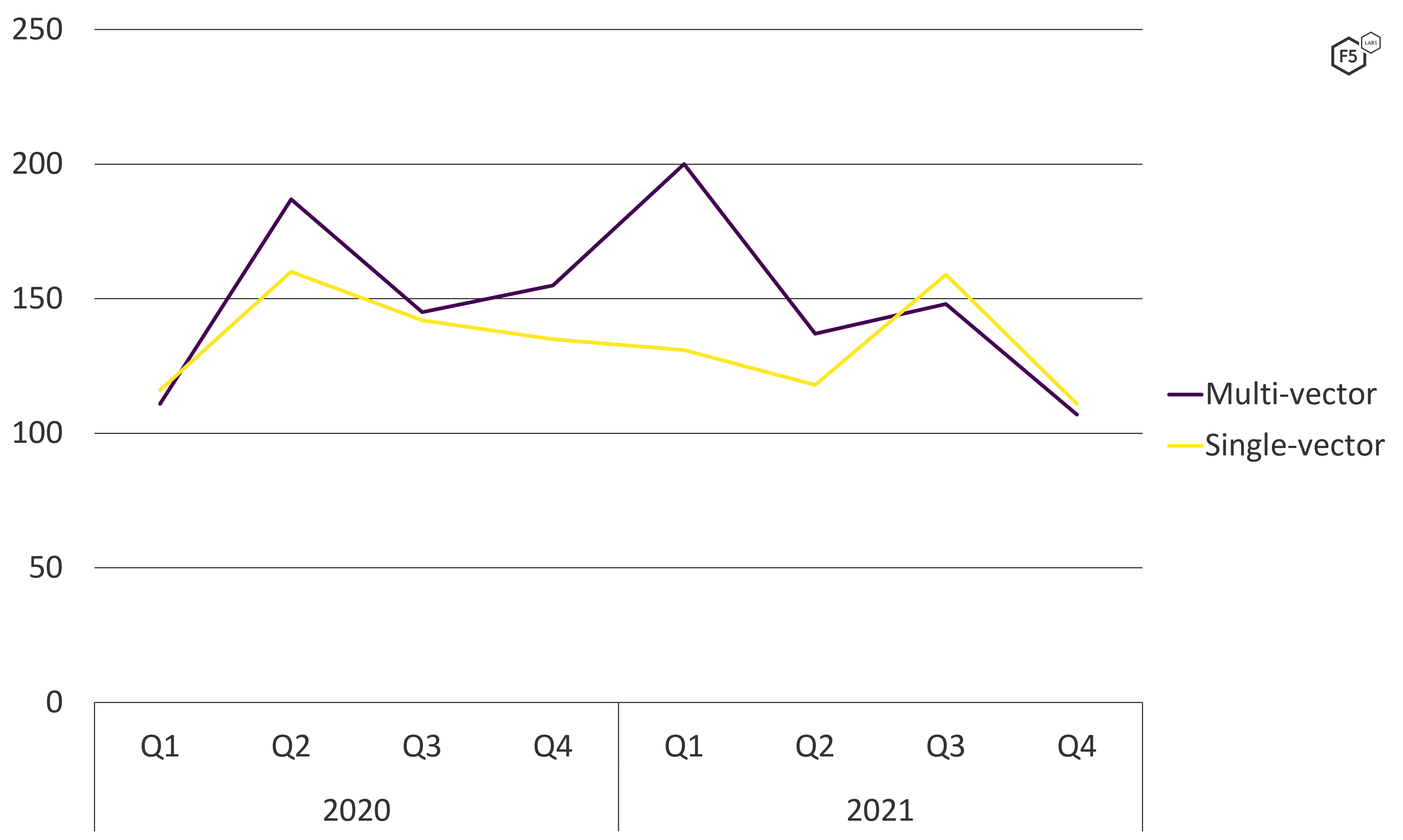

Multivectored attacks like these are common. The more vectors used, the more techniques defenders must employ to prevent a denial of service. The start of 2021 saw a much greater number of multivectored DDoS attacks compared with single-vector assaults. This leveled out toward the end of 2021, when there were an almost identical number of single and multivector attacks (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. A comparison of single-vectored and multivectored attacks over 2020 and 2021.

Emerging Attack Methods

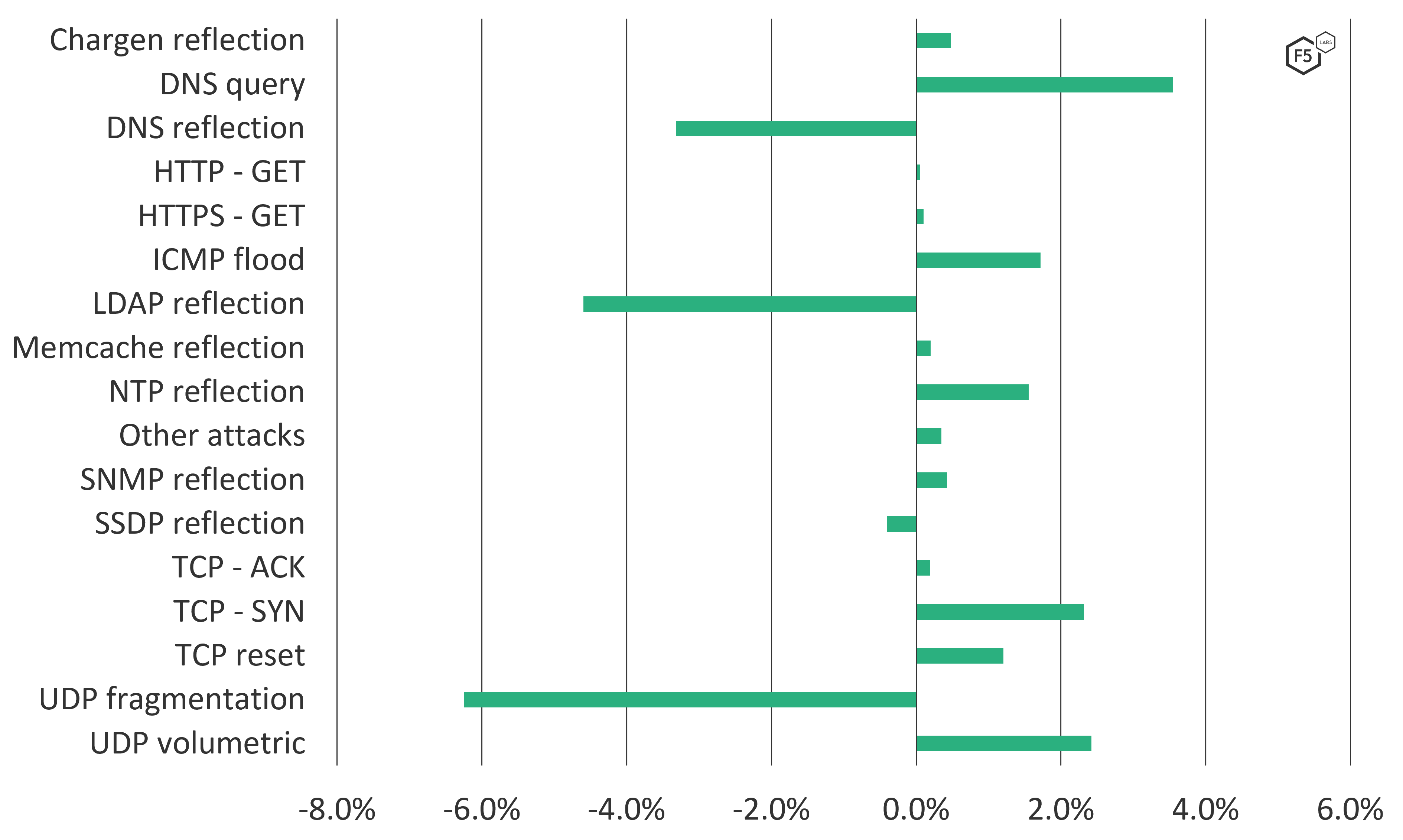

Examining the common attack methods (see Figure 6) does not tell us the whole story. Comparing each attack type’s growth or decline in popularity can be a useful indicator as to how attackers are changing their tooling and adapting to ever-improving DDoS defenses.

When examining year-on-year change it is tempting to calculate the percentage of change in the number of attacks for each type. However, we feel that this can result in misleading figures, which may cause incorrect threat assessments to be made. For example, comparing in isolation the number of SNMP reflection attacks from 2020 to 2021 we found a growth of 129%—by far the largest growth in any of the DDoS attack types. However, SNMP reflection attacks are actually a low percentage of overall attacks the F5 Security Operations Center observed. Instead, as shown in Figure 8, we compare the change in percentage values from year to year. This still reflects the growth or decline of each method but, we feel, better reflects the likelihood of this method being used in an attack.

Figure 8. Percentage of change in DDoS attack methods from 2020 to 2021.

Using this process, we observed that the most significant change in attack types was the growth of DNS queries. Unlike DNS reflection, which attempts to overwhelm network bandwidth with an overwhelming number of f reflected DNS replies, DNS queries attempt to overwhelm the DNS server itself, preventing legitimate users from resolving a domain, such as www.f5labs.com to its IP address, 107.162.154.83.

When evaluating the most common DDoS attack types and how they change over time, it is important to review both the current most common types as well as how they’ve changed. Reviewing only the changes over the past year may lead to us to conclude that DNS reflection attacks are becoming significantly less popular (see Figure 6). While their relative numbers have dropped, we should remember that DNS reflection attacks were still the second most popular attack method in 2021 (see Figure 6).

DDoS Attacks in 2021 by Industry Sector

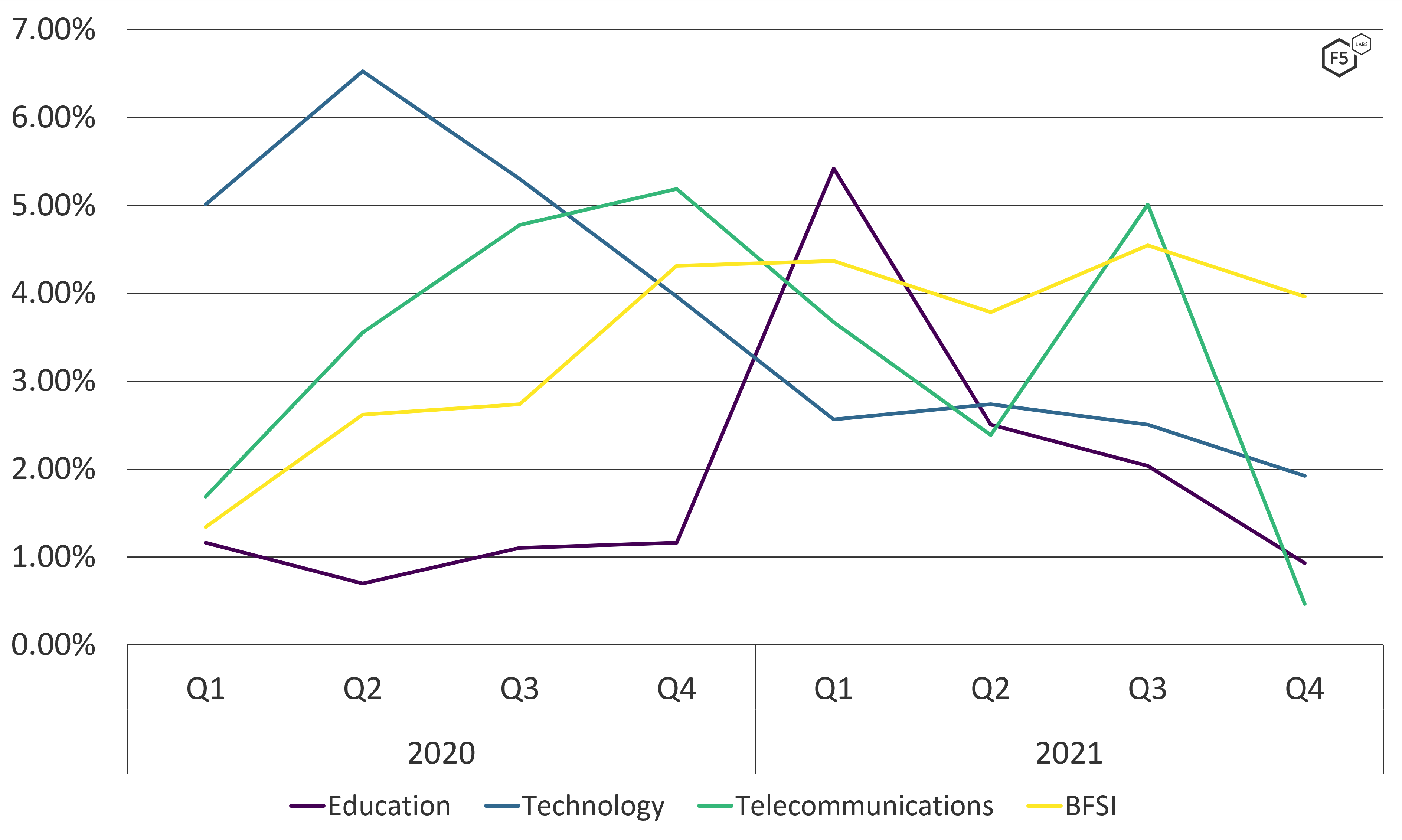

The DDoS Attack Trends for 2020 report noted that the technology sector was the most heavily impacted by denial-of-service attacks. In 2021, we found a shift in attacker focus and examined how DDoS tactics differed by target industry.

Most Targeted Industry Overall

In 2021, banking, financial services, and insurance (BFSI) organizations were the most targeted, with just over 25% of all attacks (see Figure 9). The number of attacks the finance sector sustained did not vary significantly throughout 2021, although, as observed in Figure 10, the frequency of attacks against BFSI has been growing steadily over the past two years.

Not all sectors have seen such growth, however. The technology sector has seen a steady decline in the quantity of attacks, and the education sector continues to see the most attacks at the start of new terms in September and January (see Figure 10).

Figure 10. Frequency of DDoS attacks against the education, technology, telecommunications, and BFSI sectors in 2020 and 2021.

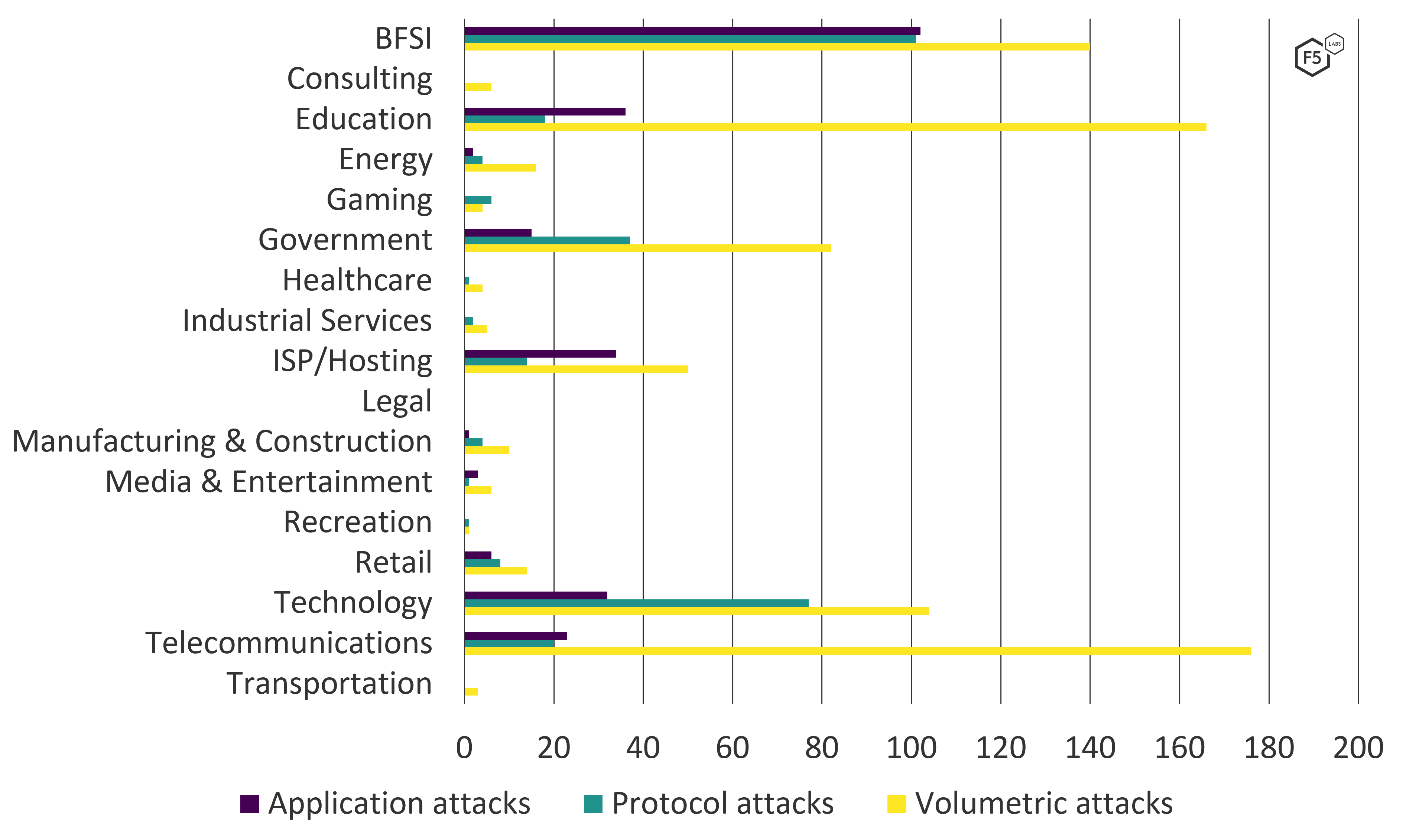

Most Targeted Industry by DDoS Type

While the BFSI sector saw the greatest total number of attacks over 2021, diving into DDoS types and methods presents a slightly different picture. Figure 11 shows the number of application, protocol, and volumetric DDoS attacks against each industry sector. Note that a single DDoS attack may be multivectored and use one or all three DDoS types.

The education sector and, in particular, the telecommunications industry, experienced a significantly higher proportion of volumetric DDoS attacks compared with protocol and application-layer ones.

Figure 11. Comparing the frequency of DDoS attack types per industry sector in 2021.

Largest Attacks by Industry

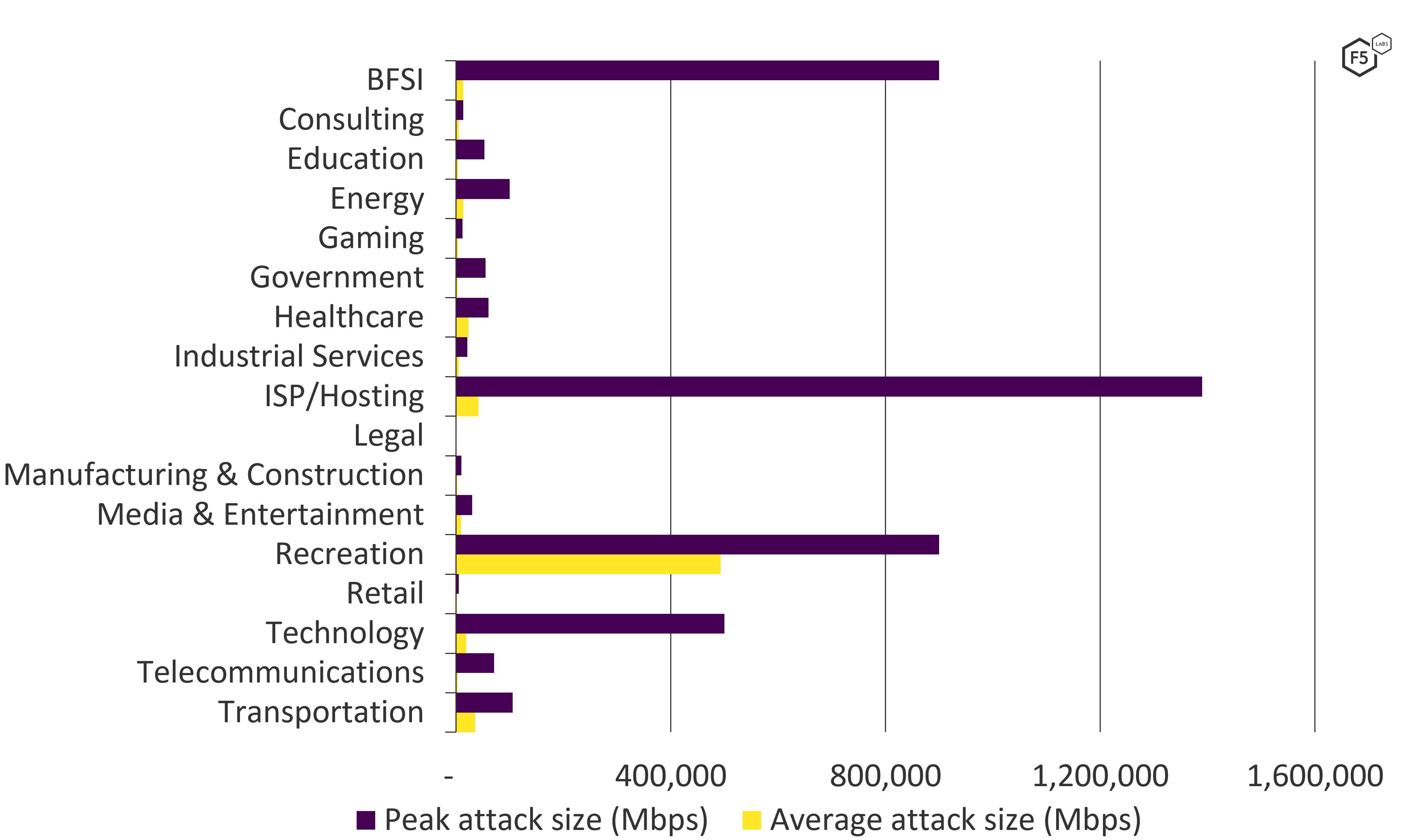

As well as suffering the greatest number of attacks, the BFSI sector is also the target of some of the largest attacks of 2021. While the average attack size for BFSI in 2021 was 13 Gbps, the sector’s largest attack peaked at 900 Gbps.

Interestingly, the recreation sector not only takes joint second place for largest attack of 2021 but takes the top spot for the highest average attack size. The mean bandwidth of attacks targeting the recreation sector was 493 Gbps (see Figure 12).

Figure 12. Average and peak attack sizes per industry sector in 2021.

The sector with the largest single attack in 2021, however, was ISP/Hosting, which saw attacks peak at 1.4 Tbps.

Where DDoS Attacks Come From

Denial-of-service attacks are most frequently launched from compromised servers or consumer devices, such as Internet-of-Thing (IoT) products and broadband routers.

In producing this report, we made use of data not only from F5’s Silverline DDoS scrubbing service but also attack data captured by our partner Effluxio. What we discovered was a fascinating attack campaign targeting a well-known consume router brand. This research is ongoing and will feature in an upcoming article.

Conclusions and Considerations

Despite a small drop in the number of attacks in 2021 compared with 2020, DDoS attacks are not abating. Far from it. They are growing in both size and complexity. Attackers are using volumetric network denial-of-service (T1498) attacks to mask the more complex protocol and application endpoint (T1499) techniques.

With many DDoS attacks lasting less than an hour, and some only a few minutes, it is reasonable to question the efficacy and, therefore, the motivation of attackers. But threat actors know that even a short interruption to a service can have dramatic consequences. A well-timed attack could interrupt a timed product launch, disrupt ticket sales, and impact brand and reputation. Alternatively, a short-lived but high-bandwidth attack could cause the victim to incur a large network bill from their cloud or hosting provider.

Beyond this, the motivation behind DDoS attacks remains varied. Nation-states continue to use these to taunt political adversaries and attack their critical national infrastructure, while students take out petty grudges against educational institutions. Organized crime groups make widespread use of denial-of-service attacks to threaten and extort their targets. Criminals use the threat of DDoS attacks to extort a ransom from their victims as well as to further harass the subject of an ongoing ransomware attack.

Today, denial-of-service attacks can be mitigated by using a DDoS mitigation service. Risk cannot be fully off-loaded, however, and so a truly effective solution will involve the use of a managed service working in close collaboration with internal application and network security teams. The “Recommended Mitigations” section that follows goes into more detail about how each control can help differing DDoS attack techniques.

Recommended Mitigations

The MITRE ATT&CK framework has an extremely short list of recommended mitigations to control DDoS attacks, in fact, only one:

Filter Network Traffic (M1037)

The crux of this control is to prevent malicious traffic from reaching your network, devices, or services before it can do any harm. Typically, this requires upstream controls which make use ISPs, cloud security services, or content delivery networks to inspect and limit the amount of traffic that reaches the endpoints (web servers).

Despite using the term network, this mitigation method refers to the identification, inspection, and control of not just network packets but application traffic too. To do this effectively, it is important to understand your web app and APIs. Which web pages or database queries cause heavy CPU or memory utilization? A worthy DDoS cloud-scrubbing service should be able to automatically detect increased latency to back-end services and apply controls, such as rate limiting, CAPTCHA enforcement, or IP address–based blocking. However, having a deep understanding of your application will allow for fine-tuned controls that will limit the impact to legitimate customers.

The following technical/preventive security controls are recommended to protect against DDoS attacks:

- Implement DDoS protection using an on-premises solution, DDoS scrubbing service, or hybrid.

- Use both network and web application firewalls.

- Use antivirus solutions to curb malware infections.

- Use a network-based intrusion-detection system.

- Apply patches promptly.

- Block traffic with spoofed source IP addresses.

- Use rate limiting to restrict the volume of incoming traffic.

Want to discuss this article with the author, other readers, and technology professionals? Head over to the F5 Community site: https://community.f5.com/t5/tkb/workflowpage/tkb-id/TechnicalArticles/article-id/13111 (Discussions cover all opinions and solutions, not just F5.)