Featured Blog Posts

F5 Ecosystem | 11/19/2025

F5 ADSP Partner Program streamlines adoption of F5 platform

The new F5 ADSP Partner Program creates a dynamic ecosystem that drives growth and success for our partners and customers.

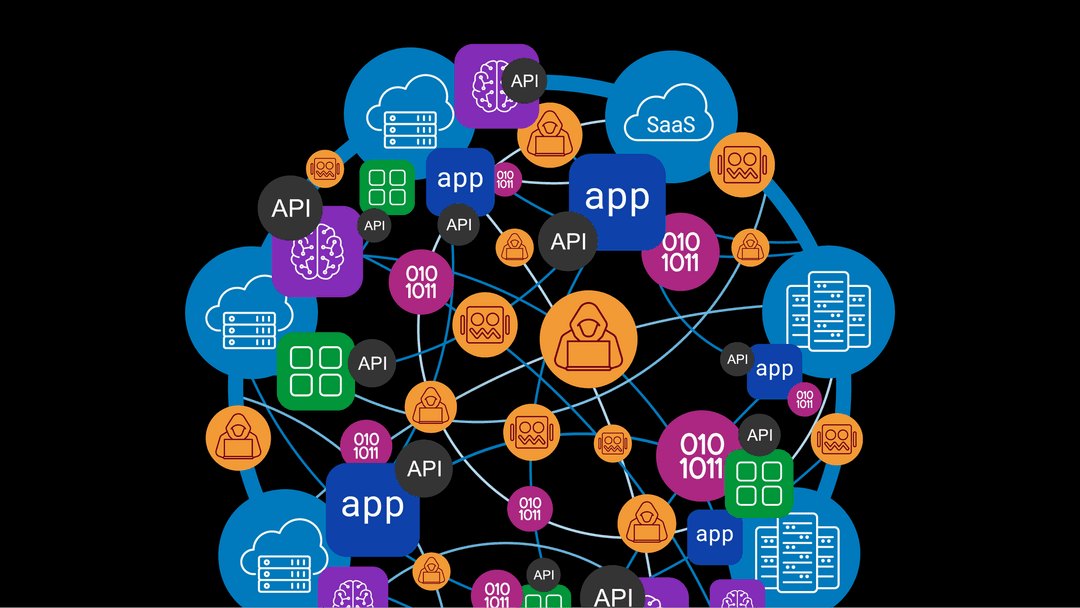

F5 ADSP | 11/18/2025

F5 BIG-IP v21.0: Control plane, AI data delivery and security enhancements

Learn how F5's BIG-IP v21.0 transforms AI app delivery and security with modernized solutions for control plane, server reliability, & application scalability.

F5 ADSP | 12/05/2025

F5 named a leader in KuppingerCole’s Generative AI Defense Leadership Compass

KuppingerCole names F5 an innovation, market, and product leader in its inaugural Generative AI Defense (GAD) Leadership Compass.

All Blog Posts

(1835)Sort By: