Improving web application performance is more critical than ever. The share of economic activity that’s online is growing; more than 5% of the developed world’s economy is now on the Internet (see Resources for Internet Statistics below). And our always‑on, hyper‑connected modern world means that user expectations are higher than ever. If your site does not respond instantly, or if your app does not work without delay, users quickly move on to your competitors.

For example, a study done by Amazon almost 10 years ago proved that, even then, a 100‑millisecond decrease in page‑loading time translated to a 1% increase in its revenue. Another recent study highlighted the fact that that more than half of site owners surveyed said they lost revenue or customers due to poor application performance.

How fast does a website need to be? For each second a page takes to load, about 4% of users abandon it. Top ecommerce sites offer a time to first interaction ranging from one to three seconds, which offers the highest conversion rate. It’s clear that the stakes for web application performance are high and likely to grow.

Wanting to improve performance is easy, but actually seeing results is difficult. To help you on your journey, this blog post offers you ten tips to help you increase your website performance by as much as 10x. It’s the first in a series detailing how you can increase your application performance with the help of some well‑tested optimization techniques, and with a little support from NGINX. This series also outlines potential improvements in security that you can gain along the way.

Tip 1 – Accelerate and Secure Applications with a Reverse Proxy Server

If your web application runs on a single machine, the solution to performance problems might seem obvious: just get a faster machine, with more processor, more RAM, a fast disk array, and so on. Then the new machine can run your WordPress server, Node.js application, Java application, etc., faster than before. (If your application accesses a database server, the solution might still seem simple: get two faster machines, and a faster connection between them.)

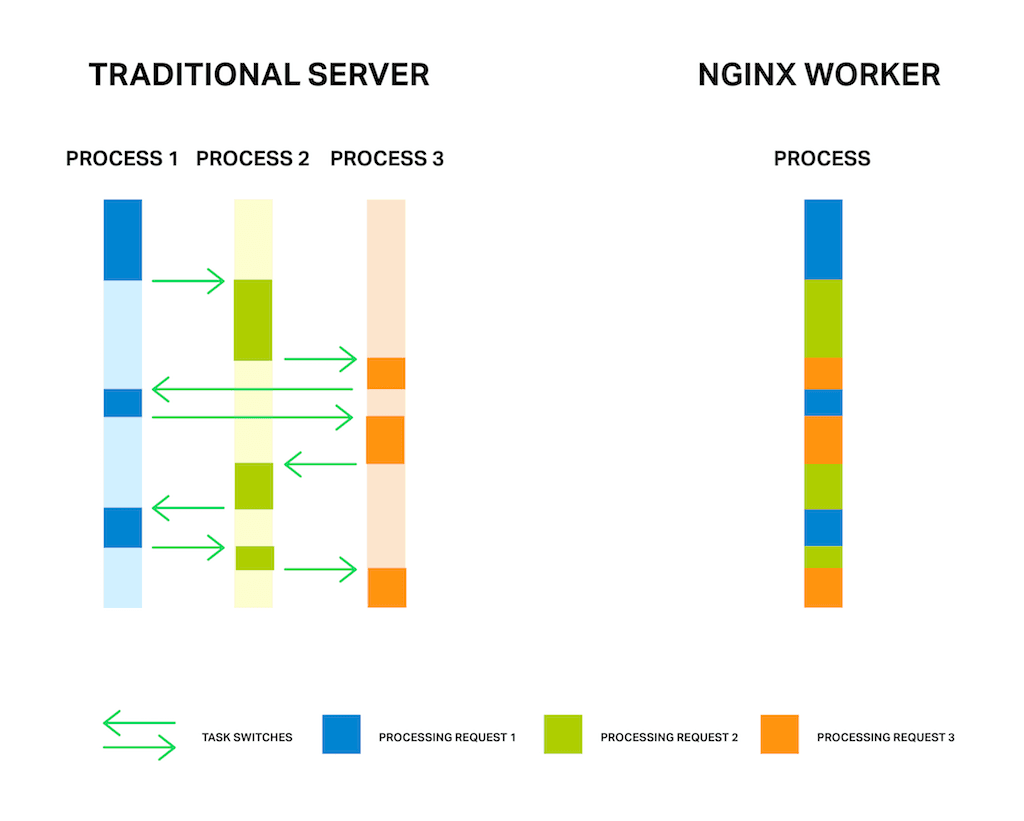

Trouble is, machine speed might not be the problem. Web applications often run slowly because the computer is switching among different kinds of tasks: interacting with users on thousands of connections, accessing files from disk, and running application code, among others. The application server may be thrashing – running out of memory, swapping chunks of memory out to disk, and making many requests wait on a single task such as disk I/O.

Instead of upgrading your hardware, you can take an entirely different approach: adding a reverse proxy server to offload some of these tasks. A reverse proxy server sits in front of the machine running the application and handles Internet traffic. Only the reverse proxy server is connected directly to the Internet; communication with the application servers is over a fast internal network.

Using a reverse proxy server frees the application server from having to wait for users to interact with the web app and lets it concentrate on building pages for the reverse proxy server to send across the Internet. The application server, which no longer has to wait for client responses, can run at speeds close to those achieved in optimized benchmarks.

Adding a reverse proxy server also adds flexibility to your web server setup. For instance, if a server of a given type is overloaded, another server of the same type can easily be added; if a server is down, it can easily be replaced.

Because of the flexibility it provides, a reverse proxy server is also a prerequisite for many other performance‑boosting capabilities, such as:

- Load balancing (see Tip 2) – A load balancer runs on a reverse proxy server to share traffic evenly across a number of application servers. With a load balancer in place, you can add application servers without changing your application at all.

- Caching static files (see Tip 3) – Files that are requested directly, such as image files or code files, can be stored on the reverse proxy server and sent directly to the client, which serves assets more quickly and offloads the application server, allowing the application to run faster.

- Securing your site – The reverse proxy server can be configured for high security and monitored for fast recognition and response to attacks, keeping the application servers protected.

NGINX software is specifically designed for use as a reverse proxy server, with the additional capabilities described above. NGINX uses an event‑driven processing approach which is more efficient than traditional servers. NGINX Plus adds more advanced reverse proxy features, such as application health checks, specialized request routing, advanced caching, and support.

Tip 2 – Add a Load Balancer

Adding a load balancer is a relatively easy change which can create a dramatic improvement in the performance and security of your site. Instead of making a core web server bigger and more powerful, you use a load balancer to distribute traffic across a number of servers. Even if an application is poorly written, or has problems with scaling, a load balancer can improve the user experience without any other changes.

A load balancer is, first, a reverse proxy server (see Tip 1) – it receives Internet traffic and forwards requests to another server. The trick is that the load balancer supports two or more application servers, using a choice of algorithms to split requests between servers. The simplest load balancing approach is round robin, with each new request sent to the next server on the list. Other methods include sending requests to the server with the fewest active connections. NGINX Plus has capabilities for continuing a given user session on the same server, which is called session persistence.

Load balancers can lead to strong improvements in performance because they prevent one server from being overloaded while other servers wait for traffic. They also make it easy to expand your web server capacity, as you can add relatively low‑cost servers and be sure they’ll be put to full use.

Protocols that can be load balanced include HTTP, HTTPS, SPDY, HTTP/2, WebSocket, FastCGI, SCGI, uwsgi, memcached, and several other application types, including TCP‑based applications and other Layer 4 protocols. Analyze your web applications to determine which you use and where performance is lagging.

The same server or servers used for load balancing can also handle several other tasks, such as SSL termination, support for HTTP/1.x and HTTP/2 use by clients, and caching for static files.

NGINX is often used for load balancing. To learn more, download our ebook, Five Reasons to Choose a Software Load Balancer. You can get basic configuration instructions in Load Balancing with NGINX and NGINX Plus, Part 1, and full documentation in the NGINX Plus Admin Guide. NGINX Plus is our commercial product and supports more specialized load balancing features such as load routing based on server response time and the ability to load balance on Microsoft’s NTLM protocol.

Tip 3 – Cache Static and Dynamic Content

Caching improves web application performance by delivering content to clients faster. Caching can involve several strategies: preprocessing content for fast delivery when needed, storing content on faster devices, storing content closer to the client, or a combination.

There are two different types of caching to consider:

- Caching of static content – Infrequently changing files, such as image files (JPEG, PNG) and code files (CSS, JavaScript), can be stored on an edge server for fast retrieval from memory or disk.

- Caching of dynamic content – Many Web applications generate fresh HTML for each page request. By briefly caching one copy of the generated HTML for a brief period of time, you can dramatically reduce the total number of pages that have to be generated while still delivering content that’s fresh enough to meet your requirements.

If a page gets 10 views per second, for instance, and you cache it for 1 second, 90% of requests for the page will come from the cache. If you separately cache static content, even the freshly generated versions of the page might be made up largely of cached content.

There are three main techniques for caching content generated by web applications:

- Moving content closer to users – Keeping a copy of content closer to the user reduces its transmission time.

- Moving content to faster machines – Content can be kept on a faster machine for faster retrieval.

- Moving content off of overused machines – Machines sometimes operate much slower than their benchmark performance on a particular task because they are busy with other tasks. Caching on a different machine improves performance for the cached resources and also for noncached resources, because the host machine is less overloaded.

Caching for web applications can be implemented from the inside – the web application server – out. First, caching is used for dynamic content, to reduce the load on application servers. Then, caching is used for static content (including temporary copies of what would otherwise be dynamic content), further off‑loading application servers. And caching is then moved off of application servers and onto machines that are faster and/or closer to the user, unburdening the application servers, and reducing retrieval and transmission times.

Improved caching can speed up applications tremendously. For many web pages, static data, such as large image files, makes up more than half the content. It might take several seconds to retrieve and transmit such data without caching, but only fractions of a second if the data is cached locally.

As an example of how caching is used in practice, NGINX and NGINX Plus use two directives to set up caching: proxy_cache_path and proxy_cache. You specify the cache location and size, the maximum time files are kept in the cache, and other parameters. Using a third (and quite popular) directive, proxy_cache_use_stale, you can even direct the cache to supply stale content when the server that supplies fresh content is busy or down, giving the client something rather than nothing. From the user’s perspective, this may strongly improves your site or application’s uptime.

NGINX Plus has advanced caching features, including support for cache purging and visualization of cache status on a dashboard for live activity monitoring.

For more information on caching with NGINX, see the reference documentation and the NGINX Plus Admin Guide.

Note: Caching crosses organizational lines between people who develop applications, people who make capital investment decisions, and people who run networks in real time. Sophisticated caching strategies, like those alluded to here, are a good example of the value of a DevOps perspective, in which application developer, architectural, and operations perspectives are merged to help meet goals for site functionality, response time, security, and business results, )such as completed transactions or sales.

Tip 4 – Compress Data

Compression is a huge potential performance accelerator. There are carefully engineered and highly effective compression standards for photos (JPEG and PNG), videos (MPEG‑4), and music (MP3), among others. Each of these standards reduces file size by an order of magnitude or more.

Text data – including HTML (which includes plain text and HTML tags), CSS, and code such as JavaScript – is often transmitted uncompressed. Compressing this data can have a disproportionate impact on perceived web application performance, especially for clients with slow or constrained mobile connections.

That’s because text data is often sufficient for a user to interact with a page, where multimedia data may be more supportive or decorative. Smart content compression can reduce the bandwidth requirements of HTML, Javascript, CSS and other text‑based content, typically by 30% or more, with a corresponding reduction in load time.

If you use SSL, compression reduces the amount of data that has to be SSL‑encoded, which offsets some of the CPU time it takes to compress the data.

Methods for compressing text data vary. For example, see the Tip 6 for a novel text compression scheme in SPDY and HTTP/2, adapted specifically for header data. As another example of text compression you can turn on GZIP compression in NGINX. After you pre‑compress text data on your services, you can serve the compressed .gz file directly using the gzip_static directive.

Tip 5 – Optimize SSL/TLS

The Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) protocol and its successor, the Transport Layer Security (TLS) protocol, are being used on more and more websites. SSL/TLS encrypts the data transported from origin servers to users to help improve site security. Part of what may be influencing this trend is that Google now uses the presence of SSL/TLS as a positive influence on search engine rankings.

Despite rising popularity, the performance hit involved in SSL/TLS is a sticking point for many sites. SSL/TLS slows website performance for two reasons:

- The initial handshake required to establish encryption keys whenever a new connection is opened. The way that browsers using HTTP/1.x establish multiple connections per server multiplies that hit.

- Ongoing overhead from encrypting data on the server and decrypting it on the client.

To encourage the use of SSL/TLS, the authors of HTTP/2 and SPDY (described in the next Tip) designed these protocols so that browsers need just one connection per browser session. This greatly reduces one of the two major sources of SSL overhead. However, even more can be done today to improve the performance of applications delivered over SSL/TLS.

The mechanism for optimizing SSL/TLS varies by web server. As an example, NGINX uses OpenSSL, running on standard commodity hardware, to provide performance similar to dedicated hardware solutions. NGINX SSL performance is well‑documented and minimizes the time and CPU penalty from performing SSL/TLS encryption and decryption.

In addition, see this blog post for details on ways to increase SSL/TLS performance. To summarize briefly, the techniques are:

- Session caching – Uses the

ssl_session_cachedirective to cache the parameters used when securing each new connection with SSL/TLS. - Session tickets or IDs – These store information about specific SSL/TLS sessions in a ticket or ID so a connection can be reused smoothly, without new handshaking.

- OCSP stapling – Cuts handshaking time by caching SSL/TLS certificate information.

NGINX and NGINX Plus can be used for SSL/TLS termination – handling encryption and decyption for client traffic, while communicating with other servers in clear text. To set up NGINX or NGINX Plus to handle SSL/TLS termination, see the instructions for HTTPS connections and encrypted TCP connections.

Tip 6 – Implement HTTP/2 or SPDY

For sites that already use SSL/TLS, HTTP/2 and SPDY are very likely to improve performance, because the single connection requires just one handshake. For sites that don’t yet use SSL/TLS, HTTP/2 and SPDY makes a move to SSL/TLS (which normally slows performance) a wash from a responsiveness point of view.

Google introduced SPDY in 2012 as a way to achieve faster performance on top of HTTP/1.x. HTTP/2 is the recently approved IETF standard based on SPDY. SPDY is broadly supported, but is soon to be deprecated, replaced by HTTP/2.

The key feature of SPDY and HTTP/2 is the use of a single connection rather than multiple connections. The single connection is multiplexed, so it can carry pieces of multiple requests and responses at the same time.

By getting the most out of one connection, these protocols avoid the overhead of setting up and managing multiple connections, as required by the way browsers implement HTTP/1.x. The use of a single connection is especially helpful with SSL, because it minimizes the time‑consuming handshaking that SSL/TLS needs to set up a secure connection.

The SPDY protocol required the use of SSL/TLS; HTTP/2 does not officially require it, but all browsers so far that support HTTP/2 use it only if SSL/TLS is enabled. That is, a browser that supports HTTP/2 uses it only if the website is using SSL and its server accepts HTTP/2 traffic. Otherwise, the browser communicates over HTTP/1.x.

When you implement SPDY or HTTP/2, you no longer need typical HTTP performance optimizations such as domain sharding, resource merging, and image spriting. These changes make your code and deployments simpler and easier to manage. To learn more about the changes that HTTP/2 is bringing about, read our white paper, HTTP/2 for Web Application Developers.

As an example of support for these protocols, NGINX has supported SPDY from early on, and most sites that use SPDY today run on NGINX. NGINX is also pioneering support for HTTP/2, with support for HTTP/2 in NGINX open source and NGINX Plus as of September 2015.

Over time, we at NGINX expect most sites to fully enable SSL and to move to HTTP/2. This will lead to increased security and, as new optimizations are found and implemented, simpler code that performs better.

Tip 7 – Update Software Versions

One simple way to boost application performance is to select components for your software stack based on their reputation for stability and performance. In addition, because developers of high‑quality components are likely to pursue performance enhancements and fix bugs over time, it pays to use the latest stable version of software. New releases receive more attention from developers and the user community. Newer builds also take advantage of new compiler optimizations, including tuning for new hardware.

Stable new releases are typically more compatible and higher‑performing than older releases. It’s also easier to keep on top of tuning optimizations, bug fixes, and security alerts when you stay on top of software updates.

Staying with older software can also prevent you from taking advantage of new capabilities. For example, HTTP/2, described above, currently requires OpenSSL 1.0.1. Starting in mid‑2016, HTTP/2 will require OpenSSL 1.0.2, which was released in January 2015.

NGINX users can start by moving to the latest version of NGINX or NGINX Plus; they include new capabilities such as socket sharding and thread pools (see Tip 9), and both are constantly being tuned for performance. Then look at the software deeper in your stack and move to the most recent version wherever you can.

Tip 8 – Tune Linux for Performance

Linux is the underlying operating system for most web server implementations today, and as the foundation of your infrastructure, Linux represents a significant opportunity to improve performance. By default, many Linux systems are conservatively tuned to use few resources and to match a typical desktop workload. This means that web application use cases require at least some degree of tuning for maximum performance.

Linux optimizations are web server‑specific. Using NGINX as an example, here are a few highlights of changes you can consider to speed up Linux:

- Backlog queue – If you have connections that appear to be stalling, consider increasing

net.core.somaxconn, the maximum number of connections that can be queued awaiting attention from NGINX. You will see error messages if the existing connection limit is too small, and you can gradually increase this parameter until the error messages stop. - File descriptors – NGINX uses up to two file descriptors for each connection. If your system is serving a lot of connections, you might need to increase

sys.fs.file_max, the system‑wide limit for file descriptors, andnofile, the user file descriptor limit, to support the increased load. - Ephemeral ports – When used as a proxy, NGINX creates temporary (“ephemeral”) ports for each upstream server. You can increase the range of port values, set by

net.ipv4.ip_local_port_range, to increase the number of ports available. You can also reduce the timeout before an inactive port gets reused with thenet.ipv4.tcp_fin_timeoutsetting, allowing for faster turnover.

For NGINX, check out the NGINX performance tuning guide to learn how to optimize your Linux system so that it can cope with large volumes of network traffic without breaking a sweat!

Tip 9 – Tune Your Web Server for Performance

Whatever web server you use, you need to tune it for web application performance. The following recommendations apply generally to any web server, but specific settings are given for NGINX. Key optimizations include:

- Access logging – Instead of writing a log entry for every request to disk immediately, you can buffer entries in memory and write them to disk as a group. For NGINX, add the

buffer=sizeparameter to theaccess_logdirective to write log entries to disk when the memory buffer fills up. If you add theflush=timeparameter, the buffer contents are also be written to disk after the specified amount of time. - Buffering – Buffering holds part of a response in memory until the buffer fills, which can make communications with the client more efficient. Responses that don’t fit in memory are written to disk, which can slow performance. When NGINX buffering is on, you use the

proxy_buffer_sizeandproxy_buffersdirectives to manage it. - Client keepalives – Keepalive connections reduce overhead, especially when SSL/TLS is in use. For NGINX, you can increase the maximum number of

keepalive_requestsa client can make over a given connection from the default of 100, and you can increase thekeepalive_timeoutto allow the keepalive connection to stay open longer, resulting in faster subsequent requests. - Upstream keepalives – Upstream connections – connections to application servers, database servers, and so on – benefit from keepalive connections as well. For upstream connections, you can increase

keepalive, the number of idle keepalive connections that remain open for each worker process. This allows for increased connection reuse, cutting down on the need to open brand new connections. For more information, refer to our blog post, HTTP Keepalive Connections and Web Performance. - Limits – Limiting the resources that clients use can improve performance and security. For NGINX, the

limit_connandlimit_conn_zonedirectives restrict the number of connections from a given source, whilelimit_rateconstrains bandwidth. These settings can stop a legitimate user from “hogging” resources and also help prevent against attacks. Thelimit_reqandlimit_req_zonedirectives limit client requests. For connections to upstream servers, use themax_connsparameter to theserverdirective in anupstreamconfiguration block. This limits connections to an upstream server, preventing overloading. The associatedqueuedirective creates a queue that holds a specified number of requests for a specified length of time after themax_connslimit is reached. - Worker processes – Worker processes are responsible for the processing of requests. NGINX employs an event‑based model and OS‑dependent mechanisms to efficiently distribute requests among worker processes. The recommendation is to set the value of

worker_processesto one per CPU. The maximum number ofworker_connections(512 by default) can safely be raised on most systems if needed; experiment to find the value that works best for your system. - Socket sharding – Typically, a single socket listener distributes new connections to all worker processes. Socket sharding creates a socket listener for each worker process, with the kernel assigning connections to socket listeners as they become available. This can reduce lock contention and improve performance on multicore systems. To enable socket sharding, include the

reuseportparameter on thelistendirective. - Thread pools – Any computer process can be held up by a single, slow operation. For web server software, disk access can hold up many faster operations, such as calculating or copying information in memory. When a thread pool is used, the slow operation is assigned to a separate set of tasks, while the main processing loop keeps running faster operations. When the disk operation completes, the results go back into the main processing loop. In NGINX, two operations – the

read()system call andsendfile()– are offloaded to thread pools.

Tip. When changing settings for any operating system or supporting service, change a single setting at a time, then test performance. If the change causes problems, or if it doesn’t make your site run faster, change it back.

For more about tuning an NGINX web server, see our blog post, Tuning NGINX for Performance.

Tip 10 – Monitor Live Activity to Resolve Issues and Bottlenecks

The key to a high‑performance approach to application development and delivery is watching your application’s real‑world performance closely and in real time. You must be able to monitor activity within specific devices and across your web infrastructure.

Monitoring site activity is mostly passive – it tells you what’s going on, and leaves it to you to spot problems and fix them.

Monitoring can catch several different kinds of issues. They include:

- A server is down.

- A server is limping, dropping connections.

- A server is suffering from a high proportion of cache misses.

- A server is not sending correct content.

A global application performance monitoring tool like New Relic or Dynatrace helps you monitor page load time from remote locations, while NGINX helps you monitor the application delivery side. Application performance data tells you when your optimizations are making a real difference to your users, and when you need to consider adding capacity to your infrastructure to sustain the traffic.

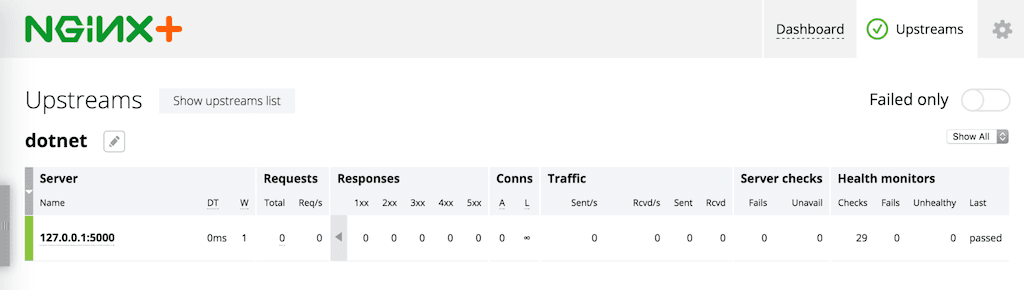

To help identify and resolve issues quickly, NGINX Plus adds application‑aware health checks – synthetic transactions that are repeated regularly and are used to alert you to problems. NGINX Plus also has session draining, which stops new connections while existing tasks complete, and a slow start capability, allowing a recovered server to come up to speed within a load‑balanced group. When used effectively, health checks allow you to identify issues before they significantly impact the user experience, while session draining and slow start allow you to replace servers and ensure the process does not negatively affect perceived performance or uptime. The figure shows the built‑in NGINX Plus live activity monitoring dashboard for a web infrastructure with servers, TCP connections, and caching.

Conclusion – Seeing 10x Performance Improvement

The performance improvements that are available for any one web application vary tremendously, and actual gains depend on your budget, the time you can invest, and gaps in your existing implementation. So, how might you achieve 10x performance improvement for your own applications?

To help guide you on the potential impact of each optimization, here are pointers to the improvement that may be possible with each tip detailed above, though your mileage will almost certainly vary:

- Reverse proxy server and load balancing – No load balancing, or poor load balancing, can cause episodes of very poor performance. Adding a reverse proxy server, such as NGINX, can prevent web applications from thrashing between memory and disk. Load balancing can move processing from overburdened servers to available ones and make scaling easy. These changes can result in dramatic performance improvement, with a 10x improvement easily achieved compared to the worst moments for your current implementation, and lesser but substantial achievements available for overall performance.

- Caching dynamic and static content – If you have an overburdened web server that’s doubling as your application server, 10x improvements in peak‑time performance can be achieved by caching dynamic content alone. Caching for static files can improve performance by single‑digit multiples as well.

- Compressing data – Using media file compression such as JPEG for photos, PNG for graphics, MPEG‑4 for movies, and MP3 for music files can greatly improve performance. Once these are all in use, then compressing text data (code and HTML) can improve initial page load times by a factor of two.

- Optimizing SSL/TLS – Secure handshakes can have a big impact on performance, so optimizing them can lead to perhaps a 2x improvement in initial responsiveness, particularly for text‑heavy sites. Optimizing media file transmission under SSL/TLS is likely to yield only small performance improvements.

- Implementing HTTP/2 and SPDY – When used with SSL/TLS, these protocols are likely to result in incremental improvements for overall site performance.

- Tuning Linux and web server software (such as NGINX) – Fixes such as optimizing buffering, using keepalive connections, and offloading time‑intensive tasks to a separate thread pool can significantly boost performance; thread pools, for instance, can speed disk‑intensive tasks by nearly an order of magnitude.

We hope you try out these techniques for yourself. We want to hear the kind of application performance improvements you’re able to achieve. Share your results in the comments below, or tweet your story with the hash tags #NGINX and #webperf!

Resources for Internet Statistics

Statista.com – Share of the internet economy in the gross domestic product in G‑20 countries in 2016

Kissmetrics – How Loading Time Affects Your Bottom Line (infographic)

Econsultancy – Site speed: case studies, tips and tools for improving your conversion rate

About the Author

Related Blog Posts

Automating Certificate Management in a Kubernetes Environment

Simplify cert management by providing unique, automatically renewed and updated certificates to your endpoints.

Secure Your API Gateway with NGINX App Protect WAF

As monoliths move to microservices, applications are developed faster than ever. Speed is necessary to stay competitive and APIs sit at the front of these rapid modernization efforts. But the popularity of APIs for application modernization has significant implications for app security.

How Do I Choose? API Gateway vs. Ingress Controller vs. Service Mesh

When you need an API gateway in Kubernetes, how do you choose among API gateway vs. Ingress controller vs. service mesh? We guide you through the decision, with sample scenarios for north-south and east-west API traffic, plus use cases where an API gateway is the right tool.

Deploying NGINX as an API Gateway, Part 2: Protecting Backend Services

In the second post in our API gateway series, Liam shows you how to batten down the hatches on your API services. You can use rate limiting, access restrictions, request size limits, and request body validation to frustrate illegitimate or overly burdensome requests.

New Joomla Exploit CVE-2015-8562

Read about the new zero day exploit in Joomla and see the NGINX configuration for how to apply a fix in NGINX or NGINX Plus.

Why Do I See “Welcome to nginx!” on My Favorite Website?

The ‘Welcome to NGINX!’ page is presented when NGINX web server software is installed on a computer but has not finished configuring